An American Society for Cybernetics event gathered those who knew her to remember the Swiss-born, London-dwelling cyberneticist, Annetta Pedretti, who died in 2018.

Pedretti was a cybernetic linguist. So conversations about Pedretti become conversations about conversations. Her writing is conscious of these conversations. It seemed that she knew that, in reading her work, and writing about it, we'd be writing a version of her into existence. In her writing, she was aware that she was writing with.

This "with" haunts me, like she's behind me, watching my keystrokes. I'll start gently then, with someone else's conversation with Annetta: Susan Parenti recalled an argument. It started when Susan said something about the “application” of theory. It ended in a verbal row with Annetta and a storming-off. Later, Susan agreed never to say “application” again, and they made up. The reasoning for the outburst was never clear. I wanted to ask Annetta about this, so I turned to her writing.

In “Against Reference,” she writes that nothing is “applied” or “practiced.” It's a false distinction from theory, because theory is and must be practice. We create theory as a practice. Theory is the application of action. They come together in writing, and action is a way to write it.

“To be and to write in the 20th century is reflected in changing from the representational relator ‘is’ to a sense of ‘being,’ as in being conscious with, or being a being rather than a thing.”

In Dialogue with Bricks

I suspect Annetta had a writing partnership with a building on Brick Lane in London. It’s in Spitalfields, a place I once knew for a goat statue, a hipster photography store, and a stretch of excellent curry shops. Today the building is the House of Annetta.

It's already historic. Over 200 years old when it burned down, save for foundations and core structure, it could not be torn down. So Annetta dedicated herself to its restoration. As a cyberneticist of language, Annetta's restoration of a building was, likely, a form of conversation.

Gerard de Zeeuw picked up this thread at the ASC event: For Annetta, language was dense with history. It references itself, wraps words in layers of interpretation and meaning-making. Words come to mean something through one another. They always point to our inner understanding of their meaning in a shared space. Language works because we understand the phrases, though each of us understands it in our own way. If we want language to be more than that internal reference, we have to listen. Ask questions, respond to answers with more questions. Through conscious listening, our internal language moves toward a shared one.

Clicks on Sticks

In Gregory Bateson’s Ecology of Mind, he describes the origin of the word “cliché." A cliché is the CTL+V for the printing press. French typesetters would speed up their process by lining up letters for frequently used turns of phrase. They arranged these phrases on sticks. They grabbed the sticks when they found the phrase in the text. Pushing the stick into the press made a clicking sound, which is what the verb clicher means: "to click."

Language, in a sense, is always a string of copied-and-pasted clichés. To communicate, every word relies on us already knowing it. “Cliché” has come to suggest a lack of engagement beyond the surface of a thought. The words are already there and the content can be easily understood, because we already know it.

But what does a word communicate? Annetta was clever enough to ask if anybody wants “easy understanding” in a conversation. A meaningful conversation should involve prying apart expected meanings to uncover intended, subjective ones.

For Pedretti, “It’s not what things are, it’s what things become when you interact with them,” de Zeeuw said. The threads of a conversation were her playground, or, in some cases, battleground. You can see it in this clip, famously brusque, explaining what a thread of conversation can be picked up, formed and reformed, and language can develop in a shared way (up to about 2:44):

How Machines Write is (Unfortunately) How Humans Listen

Texts from artificial intelligence models follow the principles of cliché. Machines arrange sentences according to statistical probabilities: words that appear together often online will appear together more often in simple language models. Today, the GPT3 model can write books using a more complex form of this concept, a richer form of autocorrect.

The AI doesn’t know what words mean, only that they fit together. We don’t place much care in the interpretation of those words. We know they are assembled for output: one after the other according to what is “supposed to” come next. Annetta suggests that this is meaningless. It is the journey from one word to the next that makes conscious thought.

Likewise, we live in an era saturated with words in all kinds of sloppy arrangements. I worry that social media has turned us into skimming machines. We look at words as “content." We signal things on timelines instead of saying them. So many words seem fit together to align with other words. Fewer seem chosen to unpack a unique experience. Our in-person, human communication suffers, too.

But this section was a meander. Let’s go back to the house.

How to Write a Building

Cybernetics is about the relationships between complex systems. Annetta was a linguist and an architect. So I am trying to see The House, and her actions in it, as a cybernetic project about relationships between systems of language and architecture.

Annetta's cybernetics were of feedback and conversation. In particular, a conversation with a structure’s 300+ year history, much of it obliterated by fire. To restore a building, to reinstate it, you have to understand it. Otherwise, it’s remodeling: a domination of the place, an “objective” that turns the house into an object.

You and I could have a conversation built around restoration of understanding between the words you use and the ones I understand, though the material is the same. To remodel my understanding of those words is indoctrination. The outgrowth of that is domination, even colonization. Restoration means creating a shared space between us where difference can be mutually navigated.

Cliché is the enemy of conversation. You say a thing you don't mean, and I interpret it according to what I already know. This is not communication. Annetta was unsympathetic to clichés, and for the writer’s reliance on them. To unravel clichés in the interest of curiosity was proof of a conscious, engaged mind. To allow clichés to sit in for experience was to drift.

So how does one enter a conversation with a building? Or with any technology, community, or act of design or intervention? Roughly, through curiosity.

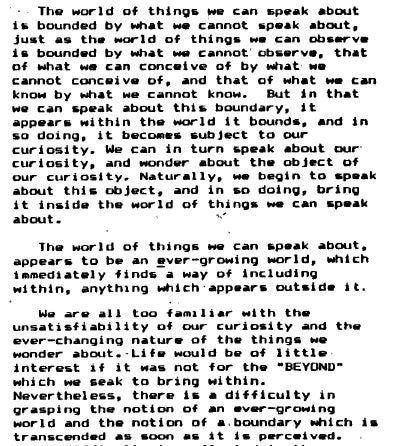

“The world of things we can speak about is bounded by what we cannot speak about, just as the world of things we can observe is bounded by what we cannot observe., that of what we can conceive of by what we cannot conceive of, and that of what we can know by what we cannot know. But in that we can speak about this boundary, it appears within the world it bounds, and in so doing, it becomes subject to our curiosity. We can in turn speak about our curiosity, and wonder about the object of our curiosity. Naturally, we begin to speak about this object, and in so doing, bring it inside the world of things we can speak about.

The world of things we can speak about appears to be an ever-growing world, which immediately finds a way of including within anything which appears outside it. We are all too familiar with the unsatisfiability of our curiosity and the ever-changing nature of the things we wonder about. Life would be of little interest if it was not for the ‘beyond’ which we seek to bring ‘within’. Nevertheless, there is a difficulty in grasping the notion of an ever-growing world and the notion of a boundary which is transcended as soon as it is perceived.” (3)

…

“It is this difficulty which underlies the difficulty in speaking about ever-growing worlds. It is not that the notion of such growth in and of itself lies beyond what we can speak about. It is rather that the dynamics of the ever-growing world of things we can speak about arises in the complementarity between what is spoken about and what, in so doing, must be passed over in silence.” (4) — Cybernetics of Language, Dissertation, 1981

We can imagine this dynamic at play in academic publishing. New knowledge references some existing knowledge. Specific language choices have already been made for the thing you’ve observed. In using that language, you confirm the past, render it into shorthand in the service of your own work.

The First Cybernetic Collapse

Here I introduce an imaginary Annetta, one constructed through her writing and my understanding of it. I’m not sure if it’s restoration or renovation. Good intentions aren’t enough to ensure one or the other. Reach now for the cliché stick that spells out: “take this with a grain of salt.”

Annetta wrote that the first wave of cybernetics couldn't pull from a book shelf or cliché sticks. The first cyberneticians spoke in that hierarchical language of scientific research, applied it to machines, and it worked. The myth of objectivity lurked over cybernetics for this reason. It reflected its preoccupation with mechanical systems and information organization.

After computers verified cybernetic concepts, it seemed to split. Suddenly, the idea of objective knowledge was embedded into a machine. Cybernetic subjectivity ended up partitioned off. The language of this second wave of cybernetics suffered from lack of reference that its external validators needed. It didn't meet standards of "scientific rigor." Nor, she said, could it.

It drifted into territories of information that tested the boundaries of "observable spaces." Cybernetics, through its second wave, saw that system dynamics included the observer. Looking out at a system while ignoring yourself within it was impossible. Who were you, and what did that mean to the system you were trying to understand?

That line of thought marked an increasing disregard for cybernetics in the "objective" sciences. This idea of position, territory, and subjectivity in the sciences was ahead of its time. Scientific publishing norms still struggle to understand the limits of objectivity. In artificial intelligence circles, the idea that race influences data is somehow still controversial. The idea that race influences the processing of data by “objective machines” remains even more so.

Part of the ostracism of cybernetics was linguistic. If everything is a system, she wrote, the term becomes meaningless. The answer of second wave cybernetics was "you draw your own boundary, and it reflects your place within it." That didn't fit the objectivity regime.

A systems consultant can't come in and tell you they will look at “everything.” There’s not enough language within “scientific consensus” to do that kind of work. Understanding systems through cybernetics shifted its “objective” posture of the first wave to a self-aware posture in its second. It moved from providing answers to providing questions that challenged answers.

In setting boundaries of a system, the observer makes subjective, sometimes intuitive decisions. We make edits, revise the universe down to fit into the design proposal: “Without a means to speak about his insight,” Annetta writes, “he was bound to appear as a visionary magician, transparently disguised as pseudo-scientist, or as a craftsman, in the best sense of the word.”

Cybernetics, in short, got "kooky." There was broad application of the term to all kinds of things, because all kinds of things were systems. The drift of boundaries led to a demand for more precision. Cybernetics got sliced up. Emergent subfields encompassed everything from AI to management studies to psychoanalysis. Along the way, that transdisciplinary aspect of cybernetics disappeared.

So, Annetta asks: if that's what happens when cybernetics is a science, what happens when it isn't? What if it was (and these are definitely my words, not hers) — a “theory written through practice”? That, perhaps, explains the building on Brick Lane.

The House that Cybernetics Built

Annetta settles on craft — an art — to explain cybernetics. A tool to study dynamic systems through cybernetic practice. That's how cybernetic knowledge gets produced. Full circle, now, as Annetta's spirit hovers over the keyboard to warn me about that word, “practice.”

The House on Brick Lane is four stories of brick. I’ve never been inside the building. I passed it on my way to the international street food pop-up that gave me cheap access to okonomiyaki when I lived in London. It’s around the corner from the Truman Brewery, home of the Rough Trade flagship store, some breweries and vegan restaurants along with a suite of creative and marketing professionals.

Annetta lived there then, but I didn’t know it, and likely wouldn’t know enough to care if I did. I didn’t know what all this stuff was about then. That’s the thing, about what’s accessible to us about the “ever-growing world" of our curiosity. You don’t know what’s on the other side of it if you don’t have the words to get you there.

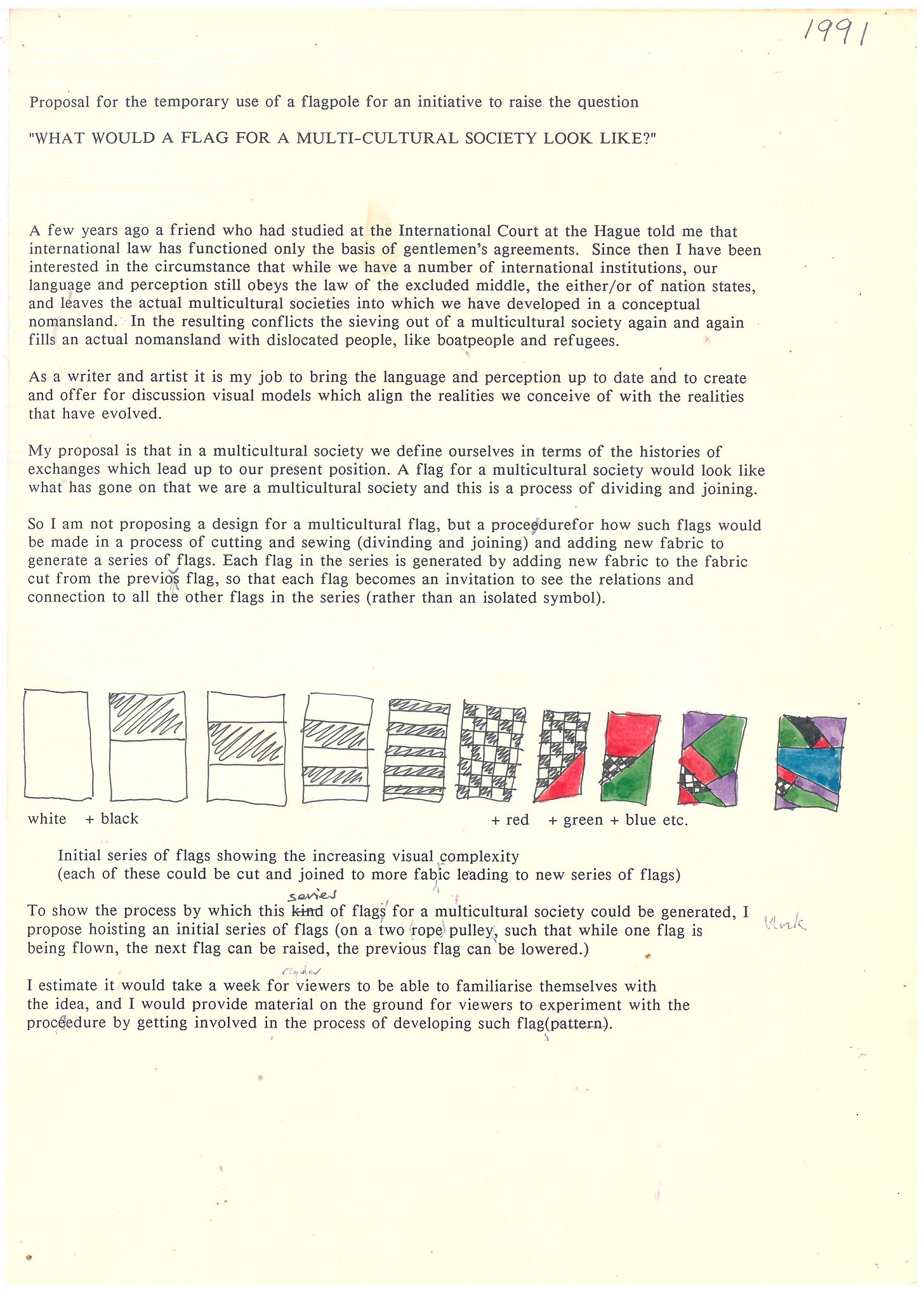

The second floor housed a printing press. Most of the space is taken up by wood, bricks, and construction tools scattered amongst keyboards and CRT monitors. The space has books and pieces of her art works. Fabric scraps, perhaps remnants of the constantly evolving multicultural flag she designed through consultation with the surrounding community in the 90s. Annetta was known for publishing and assembling hand-written books at cybernetic conferences in the late 80s and 90s. Teams of people worked all night, writing and assembling hand-written notes from questions passed along to speakers, hand-written notes of response published as-is.

Now the building is called the House of Annetta, a community space, its restoration in the midst of completion by a design collective called assemble. It’s owned by the Edith Maryon foundation, “a Swiss charity created to prevent financial speculation on land and real estate.”

Assemble runs an office on the first floor, the usable rooms are on offer to groups to organize meetings, exhibitions, and particularly, protests and campaigns against land use that uproots neighborhoods for commercial development (much of that work can be found on battleforbricklane.com, and a banner hangs from the windows of the building).

It’s easy to romanticize the house, but that does it a disservice. The house is clearly a challenge. But this fits into the sense of time and space-making that Annetta wrote about. After all, one could simply not restore a house.

Restoring a building is a way of writing the building. The building is re-emerging as the subject of a conversation with it, rather than as an object to be manipulated to the aims of its remodeler. A relationship with a building is a relationship with its systems: the history that runs through it, the infrastructure, the people living alongside it, the graffiti wall across from it. The folks passing by on their way to find a decent bagel in London just one block away. The gentrification of Shoreditch within the flows of global capital.

Annetta talks about language as a vessel for history, the unpacking of easy, off-the-shelf comprehension. That work of unraveling clichés — to ensure that you hear the words rather than what you expect them to say — requires time. Restoration is slow work. You learn from the dialogue.

“As a society we have allowed our time to be stitched up with money and a clock-work to such an extent that we allow these “constraints” on our time to oppress us almost absolutely: we can hardly escape the stress with being on time, or the pressure a dead-line with finishing in time. We have allowed the clockworks to loom (!) large in the shape of cogwheels to all but obliterate the fabric, which we only sense as the social cohesion preventing us from escaping the machine of having to make money.”

Annetta wrote about “public domain” time. It was a way of taking responsibility for time’s commodification: “To re-weave the fabric, we have to re-examine the relations in which we place time, asking, for instance, what if time makes the world go round, or if the world, rather than the clock, makes time go round?”

One of Annetta’s projects was a protest banner which doubled as a petition. Those who wanted to sign it had to stitch their names into the banner with thread. The stitching was a means to slow down the action of politics and emphasize the conversation of it. It was a way to change the relationship to time from urgent movement to slow building. It created time and space for the work of organizing.

This form of inscription weaved its way into the work on the building. It is a conversation with what remains of the structure, but also a conversation with those who come in to assist with its restoration. “It’s not about what things are,” as de Zeeuw said, “but what they become through interaction.”

Likewise, she created a community feedback process intended to develop a series of multicultural flags in 1991.

At the heart of these works were conversations. And cybernetics, at its best, should be the careful craft of cultivating conversations and relationships.

Chats

Walking away from this imagined dialogue with Annetta Pedretti, I’m pondering this definition. I think about ideas of kinship and relationship in the ways we navigate systems. How we unpack, critique, and work to unravel the expected signals of a “system” in service of what’s really there. How designing interventions in systems is meant to be a process of attention and care.

Curiosity brings things in to what can be said, expanding the border of what we don’t know. For better or for worse — depending on whether it is practiced well, or badly — cybernetics can be considered as a craft. It fuses analysis and conversations amongst systems into the work of designing between those systems. It does this in conversation with, rather than design for. Annetta’s cybernetics were a dialogue with systems, built on communicating toward a shared understanding rather than transmitting one’s understanding outward. The work is the practice that drives the theory that drives the work.

Thanks for reading! Feel free to share this post, or subscribe (it’s free!) if you haven’t already. You can also find me on Twitter: @e_salvaggio.