In 1957 the Fluxus artist George Brecht wrote Chance Imagery, a short pamphlet on the use of chance in art. He traced the idea from Dada and surrealism up to Jackson Pollock.

It is sometimes possible to specify only the universe of possible characteristics which a chance event may have. For example, a toss of a normal die will be expected to give a number from one to six. Any particular face will be expected to turn up in about one-sixth of a great many throws. But the outcome of any one toss remains unknown until the throw has been made. It is often useful to keep in mind this “universe of possible results,” even when that universe is hypothetical, for this clarifies for us the nature of our chance event as a selection from a limited universe (5).

Brecht is the creator of the “event score”, a form of instruction for the creation of specific “events” associated with Fluxus and Happenings. Brecht came to these scores through a fascination with chance, crafting minimalist sentences that suggested the unfolding of a scene. Slight variations would inevitably emerge as they moved from page to performance.

I’ve recently been given access to the OpenAI DALLE-2 beta, a machine learning tool that creates images from text prompts. I want to think about them and Brecht’s writing, because DALLE-2 replicates this score/performance dynamic.

What can Brecht’s writing on chance images and events tell us about the production of AI imagery?

Cartographies of Latent Space: How DALLE2 Works

DALLE2’s interface is a website with a text window asking what to generate. You type a description, wait about 20 seconds, and get six options. You can create variations or edit them, erasing parts and describing what to fill in. Today I am chiefly concerned with those initial images created in response to the prompt.

The images DALLE2 produces are like the roll of a die, and writing a prompt is like designing that die. The English dictionary has 171,146 entries, so a one-word prompt would be one roll of a 171,146-sided die. Combine two words and all “probable hell” breaks loose.

DALLE-2 accepts image prompts of up to 400 words. Rolling four hundred 171,146-sided dice is not a helpful metaphor for how the thing actually works. A better metaphor is space, and we have a handy bit of AI jargon. Latent space describes the scope of possible images that might be produced. Your prompt pushes the machine to assemble a puzzle made out of a map of that latent space. On that map is every possible image the model could possibly make for every possible combination of words. The prompts we write are “directions” to find what we want on that map of possibilities.

“A koala wearing a hat” draws a puzzle piece from the boxes of koalas and hats. “Wearing” is a relationship, an instruction for how those puzzle pieces are arranged: the hat goes on top of the head, and so our digital mapmaker starts looking at the koala and hat pieces. The resulting “map” of words and their relationship is only a bit random: you can not create a precise koala, only a realistic abstraction of many koalas.

DALLE2 is a “chance event” in a way that fits Brecht’s description of a “universe of possible results.” You could produce millions of images from the same prompt without replication. Brecht examined two specific modes of chance as they related to art: “one where the origin of images is unknown because it lies in deeper-than-conscious levels of the mind, and the second where images derive from mechanical processes not under the artist’s control (5).”

Today, there is some degree of confusion about the lines between these things (addressed before). It’s all too common to confuse images produced by machines with a “machinic unconscious,” even arguing that what emerges from sophisticated chance operations is a form of sentience. Brecht noted the distinction in making “chance images”: both operate from a lack of conscious design (16). An AI is a way of making chance happen, designating the results as the ones we want, and using them.

In 2019 I used OpenAI’s GPT2, a text-producing machine learning model, to make 100 Fluxus event scores, Fluxus Ex Machina. These are performances based on the George Brecht “event score” model, which were prompts for creating actions or happenings in the real world. Brecht wrote the scores as prompts, and people created them, with all kinds of variations.

In 2022, with DALLE2 capable of producing near-photo-realistic images, I returned to my Fluxus Ex Machina project, using those scores as prompts to generate images of the events they described. My original project was primed on the Fluxus Performance Workbook, a collection of scripts from everyone in the Fluxus movement. Running them through the AI (GPT2) followed the books format to generate fictional “years” for the events, which is useful in helping us place the style of photograph used in the fictional documentation.*

Fluxus scores were open to interpretation, and these results show some of the challenges DALLE2 still has in understanding conceptual and imprecise ideas. I am not saying this simply to be critical — it is a remarkable model, though with notable biases and risks of abuse. I’m simply interested in what the machine is doing and how we might frame it into a history of images and prompts more generally.

A few scores-and-image pairings follow. These examples are offered as a way of seeing what we’re talking about with regard to what DALLE2 is and does. Each image was created with the prompt format:

“Documentary footage of a Fluxus performance from [year]. [Performance score described here.]”

Grass Music

Rush into a grassy area. Dance until your movements have transformed a patch of it.

1961

Apple

Hang an apple on a tree branch.

1961

Finger Music for Cello

Cello music performance variant with a strong infusion of finger painting.

1962

In the above examples, the “maps” are drawn more or less appropriately, with images depicting more or less what was in the score. In some cases, we see some challenges.

Here are multiple images generated for the following score:

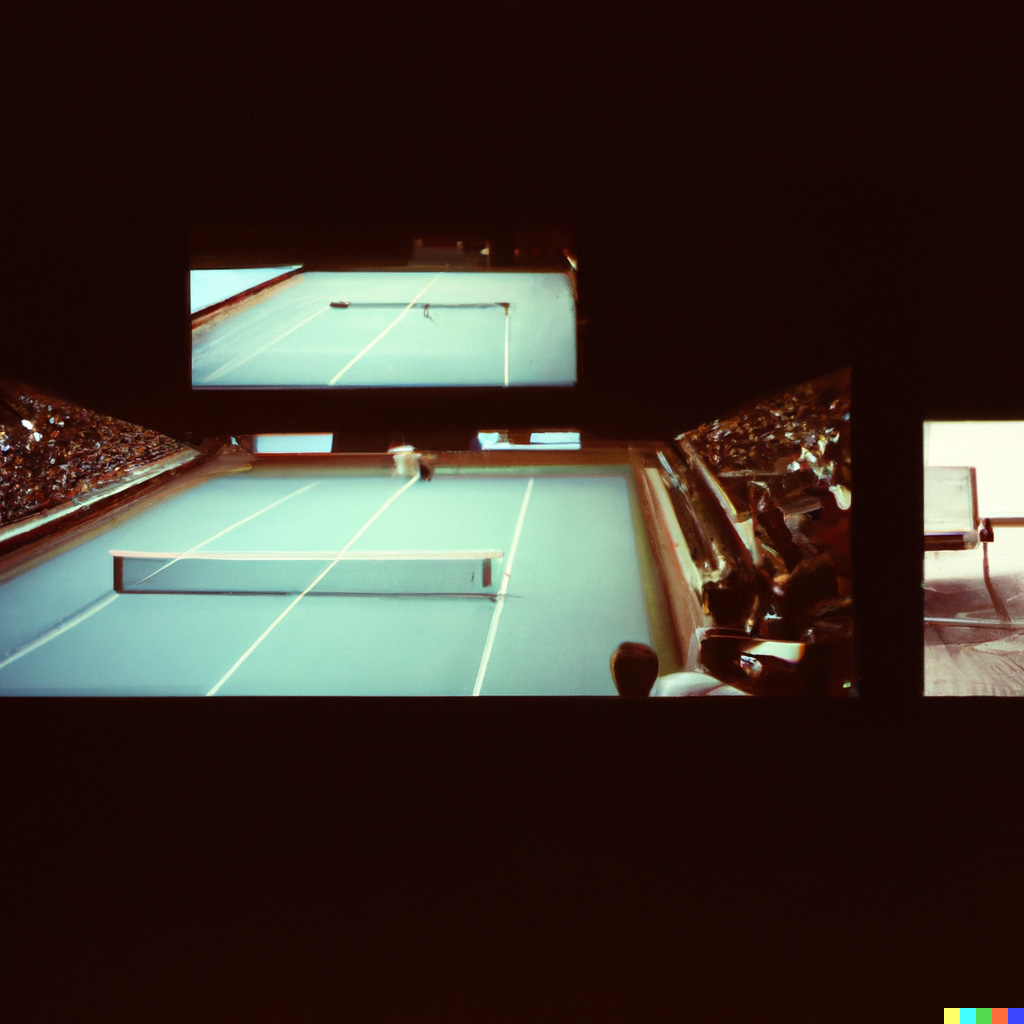

TV Game

Have a television and a television face each other, playing tennis on a court.

1966

It’s helpful to think of what DALLE2 does not as producing photographs, but as producing maps. These are coordinates of specific abstractions and their relationships which is then rendered into an image on demand, steered by our descriptions. The prompts we write offer directions to specific segments of latent space, from which the map is drawn.

When directions are imprecise, the map is imprecise. The “TV Game” event relies on linguistic ambiguity to work: “Playing tennis” on a court means playing the game of tennis, while “playing tennis” on a TV screen means to show footage of a tennis match. The confusion is deliberate, and the images show the limitations of confusion on making these maps.

Brecht covered this, too (7):

Automatism is also an aspect of chance in the sense that we accept its product as something which it really is not. In all of Breton’s manifestations of the marvelous (a handy summary) we read into phenomena characteristics which they do not possess in an absolute way. Duchamp called this “irony” (“a playful way of accepting something”), and the concept is a critical one in understanding the vector through Dada, Pollock, the present-day chance-imagists, and the future.

In 1957 Duchamp described this a bit further in his talk, The Creative Act, as the “art coefficient” which he described as “like an arithmetical relation between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed.”

DALLE2 does not understand irony, though its linguistic cousins (the GPT text-producing models) often produce unintentional irony as a result of how the English language works. For example, a text-producing GAN created the “TV Game” score, but a model from the same company using the same underlying principles has no idea how to visualize it.

On the other hand, DALLE2’s reliance on the practical, representational aspect of words and images allows it to come up with some rather elegant solutions to the open-ended and nonsensical. Consider these images produced for an Ex Machina piece that would have posed a conceptual challenge to the performer:

Balloon

Roll a balloon into the sky and then let it fly into the ground.

1987

In both images the “balloon” is “rolled into the sky” with a mechanism for letting it “fly into the ground.” One uses a tool and the other is an interpretive dance. The ways that DALLE2 solves this problem of representing concepts shows some ways that an artist might try to design a solution for this kind of prompt, which is meant to foster variety and experimentation.

Of course, I’m also reading into these images and prompts for evidence of that solution. On their own, these images may not really indicate anything of the original prompt — and my interpretation is just “a playful way of accepting something.”

Run With the Wind

Arrange string instruments in such a way that when they break, the strings land upon the surface of other strings.

1966

The goals of Brecht and OpenAI are, unsurprisingly, not aligned. Brecht was looking for ways to achieve pure randomness, because “chance in the arts provides a means for escaping the biases engrained in our personality by our culture and personal past history” (23). He wanted tools to create something new.

OpenAI — and AI designers more generally — are looking for ways of reducing randomness and producing something reliable. The rationale for Brecht, carrying the mantle from Dada and surrealism, was that human artmaking is forever influenced by human bias. The only way to eradicate human bias in art — and to produce something truly “automatic” — would be pure randomness.

Unfortunately, Brecht notes, stripping bias away from any tools designed for randomness is hard.

One might expect to avoid human bias by using mechanical systems, but experience has shown that it is not easy to find simple unbiased mechanical systems. Perfectly balanced coins and roulette wheels, like perfectly cubical and homogeneous dice, seem to occur rarely in nature, if at all. Weldon (23), for example, threw twelve dice 4096 times. For unbiased dice the probability of a 4, 5 or 6 is 1/2, so that he should have obtained one of these faces 24,576 times. These three faces actually occurred 25,145 times, which is a statistically significant bias. Even an electronic analog of a roulette wheel, built by the RAND Corporation for the generation of random digits, after careful engineering and re-engineering to eliminate bias, was found again to have statistically significant biases, after running continuously for a month, in spite of the fact that tests showed the electronic equipment itself to be in good order (24).

OpenAI’s tools have room for pure randomness, but it has moved increasingly toward legibility: it is highly and deliberately biased, because it depends on weights: it would be no good to make a map of the “koala making a hat” drawing puzzle pieces from “cats” “eating” “granola.” As the biases become stronger, and the weights become “heavier” (more reinforced), the undeliberate “irony” of these systems will be increasingly stamped out. Brecht defines randomness as “an independence of each individual choice from every other choice” — that would be catastrophic for building a commercial chat bot, or an AI for flying a plane.

As models get larger and train on more material, they become better at nuance. Each iteration also becomes potentially more constrained based on tools for intervention learned from previous systems. The Fluxus Ex Machina project, created with GPT2, is almost impossible to create using the next-gen GPT3. The newer model is simply too “good” at understanding a narrower use of language and eradicating ambiguity.

GPT3 has self-censorship mechanisms that limit possible harm. By contrast, GPT2 produced a Fluxus event score that would have created an instantly explosive chemical reaction. These constraints are laudable for eliminating racist rhetoric and misinformation uses, but implicitly narrows their usage. These limits are neccessary, but it’s the balance between weights (bias) and chance (randomness) that creates a sense of delight in creative, automatic systems.

For now, DALLE2 is doing an excellent job of “invoking chance” in its imagery, which is intoxicating. That invocation is possible because the model is so immense that the possible combinations are endlessly surprising. Brecht anticipated this in his text too:

The technique chosen for making random or chance selections in the arts is largely determined by the number and nature of the elements from which the selection is to be made. In addition, the degree of randomness of the finished image can be made as great as the artist’s desires and capabilities allow. For example, a coin can simply be tossed to determine whether a pre-selected image shall be painted in black-on-white or white-on-black, or, at the other extreme, random number tables can be used to determine the field material (canvas, paper, etc.), size and shape of the field, medium, colors, method of application of the medium (brush, drip, etc.), components of the method (brush width, applicator dimensions, etc.), and any other characteristics of interest.

What Brecht is describing is the prompt.

The Cat Sings

A cat responds to a person coming near to it.

1969

One of the questions we grapple with is whether technologies expand or restrict the human imagination. There’s concern with tools like DALLE2 for those who make a living from stock photography or illustrations — those who created the “training data” for DALLE2 by producing their art in the first place.

Brecht addressed this, too, thinking through the lens of whether chance operations would make art obsolete. As a Fluxus artist, Brecht might not have cared very much about art as a series of institutions and conservative cultural practices. He cites Robert Motherwell, calling art “a deep human necessity, not the production of a hand-made commodity” (24). Brecht goes on:

But it seems to me that we fall short of the infinite expansion of the human spirit for which we are searching, when we recognize only images which are artifacts. We are capable of more than that.

*A side note: The Fluxus artist Ken Friedman co-edited the Fluxus Performance Workbook with my undergrad mentor Owen Smith, and I briefly worked with them on a follow-up edition that was never published. In 2019 I sent the Fluxus Ex Machina scores to Ken. He made the point that in the Workbook, the years referred to the first performance, not the year they were written. For Ken, when GPT2 including the “years” for the scores, it took the project away from the world of a machine writing prompts for human performances and became a machine writing alternative history — even science fiction, perhaps even qualifying as ‘misinformation’. I’ve kept them anyway, because that’s what the AI made, though I think the contexts are richly clear. Still, I appreciated Ken’s concerns and clarifications.

Thanks for reading! As always, feel free to share if you are so inclined, and if someone recommended this newsletter to you, you can subscribe below. I’m also open to donations — buy me a cup of coffee, if you’re keen, the button works now. :)