DALLE, AARON, Kata: Strategies for Legibility

Repetition and Infusion within Image Synthesis, AI art of the 1970s, and Japanese Textiles

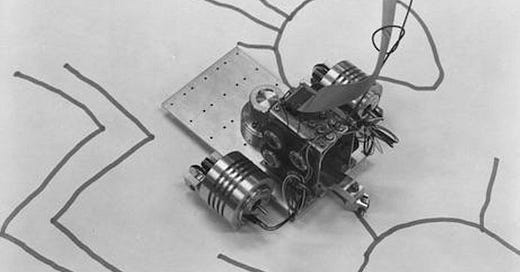

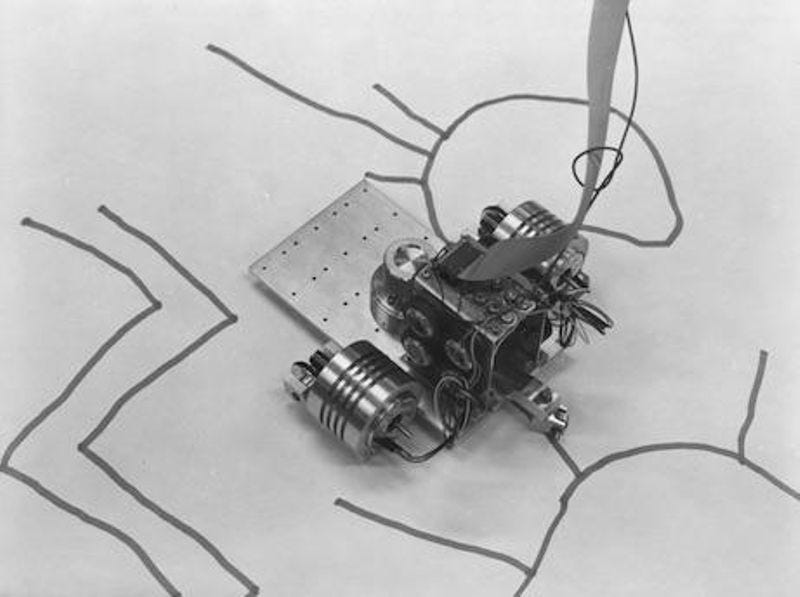

In the 1960s Harold Cohen was a painter with an impressive resume, the kind of artist who shows their work at the Venice Biennale. By the late 1960s, he began teaching art at UC San Diego. That’s where he started programming computers, working on the beautiful DEC PDP-11.

In 1970 the AI pioneer Marvin Minsky told Life Magazine that in “three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.”

In 1972 Cohen created AARON — software that could generate its own images. Once the program was running, Cohen’s art was entirely co-created with this software. He describes his motivation:

“AARON began its existence some time in the mid-seventies, in my attempt to answer what seemed then to be — but turned out not to be—a simple question. "What is the minimum condition under which a set of marks functions as an image?" On the simplest level it was not hard to propose a plausible answer: it required the spectator's belief that the marks had resulted from a purposeful human, or human-like, act. What I intended by "human-like" was that a program would need to exhibit cognitive capabilities quite like the ones we use ourselves to make and to understand images. … All its decisions about how to proceed with a drawing, from the lowest level of constructing a single line to higher-level issues of composition, were made by considering what it wanted to do in relation to what it had done already.

The first true AARON program was created with Stanford’s AI Laboratory. In those days, the approach to AI was knowledge capture: breaking activities down into a series of decisions. That chain of decisions and actions was a program. A computer that made its own decisions was “AI.”

AARON was designed to encode Cohen’s personal choices about lines and arrangements into a series of rules. When it drew a line, it was able to reference those rules to determine what the next line might be. The work varied because the starting line was randomly placed.

Today’s AI images systems do not generally work with individual artists articulating themselves in the same way. Instead, they break down images into pixel coordinates, find repeating patterns, and tap into those patterns to create “new” work. These systems “learn” how to do this, rather than being explicitly told via if/then statements, like AARON.

Nonetheless, AARON exhibited behavior that somebody would have called “sentient” if the AI hype was as strong as it is today.

Cohen wrote that AARON had a feedback mechanism: it remembered what it had drawn, and decided what to draw next based on what had come before. As a result of this feedback loop, the work it produced was novel. It also opened a path for applying machine learning for image making.

Early on, AARON presented drawings that Cohen would color in with pencils or paints; later, as Cohen expanded the code to new capabilities, the drawings became more colorful on their own.

These works - the lines, shapes, composition, and even colors - were generated algorithmically. They were not produced by the kinds of AI we see today, but defining AI is a notorious challenge.

As an artist, Cohen wasn’t interested in creating an autonomous AARON. He could have coded it to evolve, to make changes to itself, but chose not to. Compared to today, it seems more difficult to find any expressed desire for autonomous art machines during this period of history. Most artists were interested in augmentation. It may be a limit to the available technologies, or a reflection of the general ebb of interest in the technology. It may also have been the influence of cybernetics on artists, which tended to emphasize this idea of human assistance over the idea of human replacement suggested by the cybernetics-eschewing Minsky.

Nonetheless, by the 1980s, inspired by watching children draw, Cohen programmed AARON to respond to itself, starting by making its own stray (random) mark. This was the closest he got to full autonomy before losing interest and taking control back from the system.

According to an article from the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, in 1995 AARON was “one of the most creative AI programs in daily use.” They describe what AARON could do at the Boston Computer Museum (64):

“His machine would compose images of people in rooms, then draw them, mix its own dyes, and color the drawings. This exhibition turned out to be the apex of AARON’s career as an autonomous representational artist. Representational painting was evocative, but not in interesting ways, and although Cohen loved to interact with gallery audiences, he worried that the spectacle of the painting machine detracted from the art itself.”

Sounds familiar.

The Spectacle of the Painting Machine

Something I’ve noticed about AI art of the moment — the Image Synthesis Summer of 2022 — is how quickly people declare it the work of the machine, but also claim it as their own. Two weeks on Twitter and it all gets dull fast. Folks post work they made through writing a prompt, claiming they made it in collaboration with an AI. Other folks come in and say they didn’t make it, the AI did. It’s uncommon to attribute art to a tool: “Look at this sketch my pencil made” isn’t something people often say.

Cohen was the opposite.

Cohen was a painter, so his idea of art was more traditional than other artists I have written about (such as George Brecht). But he was more directly engaged in the question of machine-generated art. In a 1974 article, On Purpose, he writes:

“Any claim based upon the evidence that 'art’ has been produced would need to be examined with some care, and in the absence of any firm agreement as to what is acceptable as art we would probably want to see, at least, that the 'art' had some very fundamental characteristics in common with what we ordinarily view as art. This could not be done only on the basis of its physical characteristics: merely looking like an existing art object would not do. We would rather want to see it demonstrated that the machine behavior which resulted in the 'art’ had fundamental characteristics in common with what we know of art-making behavior.

He goes on to say:

We would probably agree, simply on the evidence that we see around us today, that the artist considers one of his functions to be the redefinition of the notion of art.

In other words: we might be tempted to evaluate art produced by machines through comparisons to what art has already been, but art, at least since the 1960s, is itself dedicated to the question of expanding what art is.

Cohen considered the relationship between artist and machine as primarily driven by purpose. An artificial intelligence program behaves with purpose. As you look at how the machine’s purpose is reflected in its decisions, however, there’s a notable distinction between himself and his machine. The machine, after all, didn’t invent a purpose for itself, as an artist would. Instead, the artist creates the machine for some purpose. The purpose, he says simply, is to draw lines. And the purpose of those lines is to make the next line.

As this system expands, is it possible to take on a sense of purpose for itself — to take over the artist’s purpose? Cohen is more complicated on that point, writing that distinguishing between the purpose of the artist and machine at higher levels of complexity “is like trying to find the largest number between zero and one: there is always another midway between the present position and the 'destination'.”

While AARON drew (literally) from a series of possible lines, I don’t see this as very different from what image synthesis models do, aside from the size of the data available to them. Obviously, today’s models are denser, and reduce things down to relationships which can then be reassembled. The size of the training data — and corresponding vastness of the parameters in the neural net — certainly enhance the complexity of what they can produce, but that alone doesn’t suggest a fundamentally different purpose from AARON.

Creativity … lay in neither the programmer alone nor in the program alone, but in the dialog between program and programmer; a dialog resting upon the special and peculiarly intimate relationship that had grown up between us over the years [9].

After Harold Cohen died, AARON was wiped out by a power surge from a lightning storm. Weird, but true.

Spiritual Diffusion

It is important to separate the idea of kinship and conscious relationships with our machines from the idea of sentience or consciousness in our machines. It’s tempting, in making sense of “what (or ‘how’) AI art means,” to go hard on the side of rejecting relationships with the tech in order to get away from claims that sentience, or real creativity, is emerging from the math.

I think we need to hold room for nuance. It’s hard for me to consider Harold Cohen wouldn’t have some kind of relationship with AARON, even if we agree that AARON is not a person.

During my time at 3AI I had the pleasure of reading, thanks to Ellen Broad, a short essay on the craft of Japanese textiles, Jenny Hall’s The Spirit in the Machine: Mutual Affinities Between Humans and Machines in Japanese Textiles. The rough thesis of that article is this:

The relationship between human beings and machines in Japanese heritage industries can be explained through two interrelated concepts. The first is the idea of technology as an extension of the human body. The second is the belief that the human spirit can be embodied within technology. Both of these concepts convey the idea that the end product somehow embodies the spirit of the artisan.

Shinto views the world as a series of interconnected relationships, connected through entangled spirits. While the “spirit,” understood in Western terms, is a ghost — individual, with personality — the spirit described by Shinto is more of a radiance, an energy emerging from a thing that gives rise to a feeling in the observer. This definition of “spirit” is embodied in all things — particularly romanticized in the awe-inspiring heft of a powerful tree or the impressive durability of a heavy stone, but also in plastic chairs and bottlecaps, when we look at them as such.

Japanese textile workers working in a traditional way will apply this to their machines, and to the items these machines produce. This “spirit” is the result of conscious effort, however. The machine extends human capability and so it extends human spirit. Through the motions of operating a loom, the spirit is infused into the fabric. Likewise, the way textiles are taught in Japan is through repetition — kata, breaking down the patterns of a master into concrete steps, like a program, which are then repeated until variation is eliminated altogether. When this happens, the spirit of the master is infused into the student. The student becomes a master artist. Slowly, from there, variations are allowed to emerge. In this way, the spirit of one’s craft lineage is infused into your production, but there remains some space for something of your own to gradually come in, like a lock of your hair finding its way into the silk.

Our relationships to image making may benefit from this perspective. AARON is a clear case of the artist being present in the work of the machine. Art critics who work in software art or computer art often focus on the code as the core of the work. Artists who write code, or artists who build their own AI models, can be more easily legible in the work they make. In Japanese textile terms, AARON takes on the spirit of Harold Cohen and extends it into the drawings and paintings.

In the GAN and Diffusion era, it’s useful to ask where this spirit resides and where it came from. These models are someone else’s machines. The fastest outputs of DALLE2, presented direct to Instagram, seem not to infuse the spirit of the poster but the spirit of the system. An artist using DALLE2 is using another weaver’s loom. On the other hand, the “maker” of the image — that is, the one who causes that creation to come forward, through the use of a prompt — is theoretically capable of infusing this “spirit” into the images. But given the complexity of DALLE2, and the minimal controls offered to those who use it, it is incredibly difficult to overcome the spirit of its lineage.

Strategies for Legibility

There has to be some way of becoming legible as an artist within the confines of DALLE2 or other ready-made image making systems. Marcel Duchamp became legible in a urinal, and Andy Warhol remained legible in screen printed reproductions of soup cans. These comparisons are a cliché of the defensive AI artist, however: a way of saying “anything can be art!” which is not a novel conversation. The question is still how can it be art, even if we all agree it can be.

One way to answer that question is through careful attention to purpose, one reflected in Harold Cohen’s relationship to AARON and in the Japanese textile worker’s relationship to the loom. We can all produce art; so instead, let’s ask: how might we infuse an artist’s spirit into our tools, and into our images?

As usual, we come back to affordances. To grow my own GAN out of someone else’s pretrained set, I would take thousands of photographs of pussy willows or seashells or human hands. The machine would trace them, replicate them, study them, and produce something from them. It’s easy to find myself in there: I conceived and took photos of those images. DALLE2 doesn’t extend us that opportunity: we have little space to enter the machine and make it our own. And for those whose data was used unknowingly by the system, a bit of that spirit was stolen.

There’s really only two ways for the artist’s purpose to enter into the images with DALLE2: through the prompt, and through selection. The prompt is where intent enters in. The selection is where the artist selects for alignment to purpose. There is another way, outside of the system, which is what we do with these images: how we decide to contextualize or recontextualize them.

When we have a relationship to one prompt and one image, it competes against a powerful spectacle of this diffusion-model “loom,” a tool built by a massively funded and educated cohort of tool-building masters of computational synthesis, and drawing from a vast but stable arrangement of associations inscribed into a particular model for image-making. Often, you can distinguish work made by DALLE2 and other diffusion models more clearly than you can distinguish work between two artists using the same tool.

It seems far more likely to find an artist “coming through” a series of a thousand images generated by the same prompt than in a single image generated from a single prompt.

One of the things I am doing with my DALLE2 artist’s access is meant to test a thesis: that an artist who makes use of a single prompt concept, thousands of times, will form a relationship with that output — a kind of kata, intended to create a relationship to a space that offers no reward to mastery.

What would I create over time if I created a thousand variations of the same prompt — while making choices over which to share and which to discard, when to adapt, sustain and evolve? Would we find some musicality in these images, placed beside images, placed beside images, marching forward over time? Or would the images simply exhaust themselves, the product of a chore rather than an art process, a one-sided relationship between myself and an unchanging machine?

Through repetition, with variation, something new might emerge: that’s the concept of feedback loops. It could be steered by my own understanding, evolve through mistakes or flashes of insight, or shift in subtle ways that are hard to account for. Or else, it may just be 1000 images.

This is one strategy I’m eager to test: to see if an artist can become legible within a hyper-active engine of infinite image production by taking advantage of that hyperactivity. So I’ll try it out. Perhaps nothing emerges — that alone would be interesting! But perhaps something does. Either way, perhaps there are some other strategies for legibility that could emerge, too.