“Post-Normal Times,” according to British-Pakistani scholar and cultural critic Ziauddin Sardar, are "in an in-between period where old orthodoxies are dying, new ones have yet to be born, and very few things seem to make sense."

Lately, for many of us, the phrase describes the exponentially rising sense that the future, though never predictable, is now just a pure, frenzied scramble. The measuring stick of yesterday as tool for approximating tomorrow feels hopelessly out of date.

In the early days of the pandemic those death charts, with their exponential curves, seemed to build a wall against any sort of insight into weeks or months from the day. Borders closed, lockdowns happened, the world was thrust into isolation, save for a screen or two connected to a few billion others, all watching The Tiger King. Time moved incrementally, followed by sudden acceleration: it could feel like Tuesday for a week straight in March, and the next day would be June. Time was messed up, and we lost all sense of “next.”

Long before all this, back in 2018, I was working at Swissnex San Francisco with Frank Vial to figure out how to articulate what the place was doing. It was bringing people together from a variety of fields, ideally to collaborate. We were looking for productive, experimental, collaborative formats to bring people and ideas together.

At the time, “Post-Normal” meant election night 2016, with its darkest timeline associations, the pollster’s barometers spinning out of control: the logic engine of prediction had broken. How do we correct the path of our over-reliance on “data” and “polling” and return to figuring things out through observation, dialogue, and ideas?

The proposition was this: if you put a bunch of people from any field into a room to brainstorm next-steps — a common foresight and design research strategy — you’re going to get something out of it. All too often, though, that something will reinforce the consensus of that field and reflect the understood trajectories of the field. Ask a bunch of people on a train which way the train is going, and they’ll likely tell you the direction it’s currently moving.

If you throw a wrench in the works, you widen the scope of that foresight / design exercise. People will suddenly have to imagine something new. That could be unexpected uses of their technologies, or new social contexts to navigate.

“The kind of futures we imagine beyond post-normal times would depend on the quality of our imagination. Given that our imagination is embedded and limited to our own culture, we will have to unleash a broad spectrum of imaginations from the rich diversity of human cultures and multiple ways of imagining alternatives to conventional, orthodox ways of being and doing.” Sardar, 2010, p. 443, via Liam Mayo’s wonderful PhD thesis, Selves and Spaces: Hacking Culture in Post Normal Times.

“Emergent Futures” was a strategy. It was based on the idea that there is more than one possible future, and that any of these futures might suddenly rise up, without much time to prepare. Emerging futures can be seen from a distance. Emergent futures, though, seem to happen all at once. They factor in exponential growth, or the human capacity for denying what’s on the horizon (good or bad). In any case, emergent futures move from over there to suddenly here. In foresight we talk about “signals,” small flags in the now that point to future possibilities. If I don’t see things coming, I suspect it’s because the way I looked for signals wasn’t wide enough, or the way I imagined signals morphing wasn’t imaginative enough.

These futures are visible to many. But for largely systemic reasons, they’re not accessible through processes tied to design or foresight. To understand “post-normal” times, we need to include people in the process who are oriented and attuned to these disruptions. For me, that’s the hacker-artists, and the activists organizing rising social movements. These are the folks who identify — or are — the “signals” before anyone else spots them, and are generating signals to make change.

Mayo writes:

“New approaches to the imagination are essential; specifically approaches that embrace anticipation in the imagining process, as a way to unlock and explore possibilities for new epistemological and ontological contexts. Here, anticipatory imagination (Bussey et al., 2017), an emergent mode of imagination that goes beyond conditioned reality, is presented as a culture hack (Bussey, 2017b); a useful process for creating and nurturing alternative stories of knowing and being in the world.”

That is to say: artists can help us imagine the world as it might be, and activists help us see the world as it is. “Culture hacking,” the activist-artist strategy of taking the pieces of the dominant culture and flipping them on their heads, is a way of showing us a different way of looking at what is. Today is tomorrow’s past. The artists’ and activists’ way of seeing “today” is the way we will see the world today in the next 5, 10, or 20 years. Why? Because they are dedicated to making that shift happen, and are on the front guard of moving it in a new direction.

I get that this sounds like co-optation, and if I was a corporate type, it likely would be. But in the context of a government agency oriented to proposing socially responsible futures through collaboration and exchange, I don’t think it is. For me, emergent futures means that the scope of design, at the earliest stages of planning “next steps,” included people who may not always be included. They may not even be born yet.

We have a responsibility to plan the future together because it is always a collective future. That goes beyond lip service and means valuing, respecting, and centering the “radical,” the “disruptive,” and the “Other.”

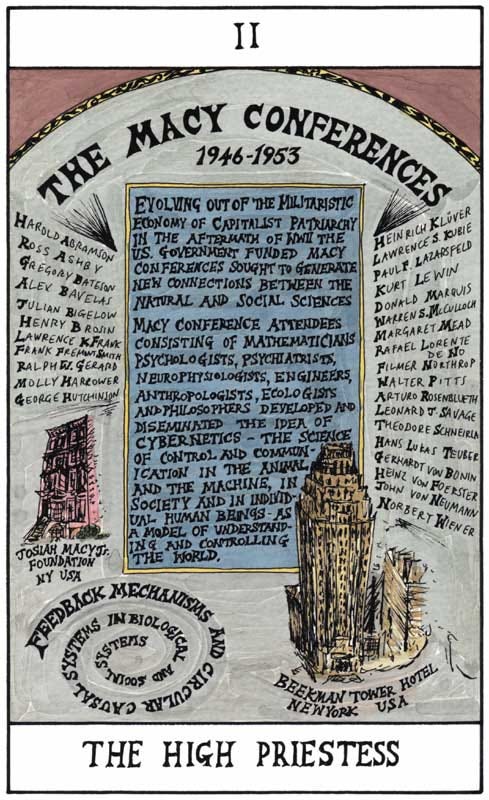

One of the foundations of Cybernetics was the Macy Conferences, a series of deliberately interdisciplinary events, starting in the 1940s. It was established to create collaboration and establish a common(ish) language for communication between scientific disciplines. The result of this was cybernetics, which ended up giving the world everything from Systems Thinking to Complexity Theory to Six Sigma Management philosophies to Machine Learning and diode-controlled South American democracies.

The initial Macy Conference concept was radical for its time: knowledge had become highly specialized, and connecting these specializations might result in something bigger than the disciplines themselves, turning an interdisciplinary conference into a transdisciplinary one (“cybernetics” being the name given to that trans-discipline).

Today, interdisciplinary thinking is a bit expected, and still beneficial. But in “post-normal” times, I worry the “expected” serves certain interests of a status quo that is changing, one way or another. I’m not the first to declare an urgent need to position inclusivity — beyond academic or design knowledge — into collaborative, speculative, future-oriented spaces.

Swissnex doesn’t use “emergent futures” in its marketing anymore, but I see that it’s since been adopted elsewhere to reflect similar positions and ideas, to varying degrees of alignment. When I did a search for the term early in the process, I didn’t find anything. I’m sure there’s some famous use of it I didn’t see that is just going to embarrass me once I send this email out. So, I’m not sure where the idea “came from”, but the language is being used in a range of places to reflect a similar constellation of ideas and suggests more than one origin, which is groovy.

My personal favorite is the Emergent Futures Co-Lab, “a transnational collective that was co-founded in Toronto, Canada and inspired immensely by Indigenous scholars and artists.” (I have no connection to them).

We are building an interconnected future and seeing things we don’t see on our own is essential. Hand an early-stage startup over to activists and artists and see what everyone learns. The results help everyone. It can anticipate damage and work to prevent it.

The ideal outcome is that the best-intentioned tech products will be broken and used in an art performance instead of taken over and co-opted by fascists or exploitative surveillance capital. Designers will hear from communities that might suffer as a result of the designed, and changes can come that eliminate social harms before being called to testify at a trial. Both of these should be powerful incentives.

Things I’m Reading This Week

###

The Limits of Design Ethics Under Capitalism

Victoria Sgarro

Relevant to the writing this week as a counter-weight.

We will not solve problems of authoritarianism, racism and xenophobia, misinformation and addictive technology, mental health and public health, or climate change with design ethics. While designers should thoroughly consider the consequences of our work, the problems facing the design and technology industry are not ones of individual bad actors (though some exist). Rather, we must acknowledge that design decisions are economic decisions — and in our current economic system, the economic interests of individuals often conflict with their social consequences. Our ability to make technology work better for society as a whole depends upon our willingness to reorder our priorities and redefine value as more than profit maximization.

###

‘What Would It Mean to Think That Thought?’: The Era of Lauren Berlant

Judith Butler, Maggie Doherty, Ajay Singh Chaudhary and Gabriel Winant

Four greats weigh in on the legacy of cultural theorist and critic Lauren Berlant.

Cruel Optimism effectively sought to describe the oscillation between manic exhilaration and devastating disappointment bound up with contemporary neoliberalism wherein the inflated expectations of what life could be are repeatedly disappointed. … Berlant was not against optimism per se, but only the cruel kind that lands you in the ditch. The work is full of hope and will remain a clarion call for all those who seek to build a sense of the world that we can all trust. But that hope cannot depend upon a false sense of inevitable progress …

The Kicker

The artist Du Kun takes sound wave data from their compositions and uses the peaks and valleys of those waves to paint landscape scrolls. It is really remarkable, and it all makes more sense in this video:

Read more about Du Kun in this article from Grace Ebert at Colossal.

Have a good week, everyone!