Ideologies of Awe & AI Art at the MoMA

Refik Anadol's Unsupervised, What Models Make Worlds, and Anatomy of an AI System.

Refik Anadol’s “Unsupervised — Machine Hallucinations” (2022) was recently acquired by the MoMA, and this weekend I got to go see it in person. Anadol is from a generation of artists that take AI literally, presenting it bathed in a constant ambient soundscape as an instrument of spiritual awe. Seeing it in the MoMA, with a series of benches set before it, feels like a contemporary Cathedral, where we may direct our awe toward a vast, ongoing data analytics visualization.

Seeing it in context, though, my reading is a bit more charitable. The work is not about AI, at least not intentionally. Anadol is using AI to mediate the building in which it is displayed — the Museum of Modern Art. It’s a GAN trained on the MoMA’s holdings. The core structure of the visualizations we see are a “latent space walk,” a video that interpolates points in between all of the data points inside the network.

Those “data points” are 180,000 images from the MoMA archive, clustered into smaller bits by visual similarity. So, drawings and sketches, for example, may be in one cluster, while photography is in another, oil paintings and pop art in others, etc. Between these, there may be some kind of overlap, but when I was there the cluster size was just 606 images. The model then interpolates new images — imagine a “slider” that phases one image into the other. The GAN can render these “in between” images across 606 images. Even a small cluster of 606 (out of 180,000) has a vast magnitude of possibilities: every image can move in 606 directions.

That is just how GANs work, but Anadol is reflecting, accurately, on the many possibilities that might be created from these in-between spaces of visual information. This is the start of the piece, and it’s one I see over-represented in discussions of the work. Latent visualizations of art archives is what GANs are for, after all, and because of the preponderance of public domain artwork online, a lot of GAN artwork did this, too: Gene Kogan’s WikiArt GAN (2018) was a walk through 80,000 oil paintings; Mario Klingemann’s Memories of Passerby (2018) used oil painting libraries to create portraits, Robbie Barrat and Obvious’ Portrait of Edmond de Belamy (2018) were in the same vein. Others have engaged in remaking and reassembling data sets from public domain works, such as Anna Ridler’s Fall of the House of Usher (2017).

Anadol adds a spider-web-like set of lines to the screen, which an observer may assume are tied to what the “blobby” images are doing. In fact, the lines respond to points in the video where motion is occuring, visualizing changes in the image as it moves from one to another. The result is an extra level of texture and depth, while the information it conveys is essentially uninformative. There’s nothing wrong with this — it adds a nice aesthetic component to what we see, and creates an important layer of texture. But it’s information that highlights what we’re already seeing on screen: the movement between one image and the next, rendered in slight advance of the movement taking place.

Anadol is doing more than linking the images in the MoMA’s catalog together. He’s linking that catalog to the physical building. Multiple data visualizations are factored into the images generated on the massive screen. Among these are the movements of people who come to look at the piece, which are abstracted and mapped as clusters of activity onscreen in ways that resemble fireworks. Weather is factored in, through data about UV index and humidity, though it was unclear to me how this data made it to what we see.

About a year ago, I consulted on the ideation phase of a project, for a major cultural institution, to envision its building as a cybernetic artwork. In those conversations, we also discussed humidity — as one mechanism for machine-controlled systems that preserved time. There were conversations about the land it sat on, its Indigenous history, how nature responded to its location and architecture. How might we turn a museum and its archives into a cybernetic system? How might we create conditions through which to access these histories and even alternative histories?

In the end, turning the building into a self-referential artwork was too complex for the time constraints. But I wish that Anadol had made some more compelling linkage between the archive, the building, the institution, and its history.

Visualizations

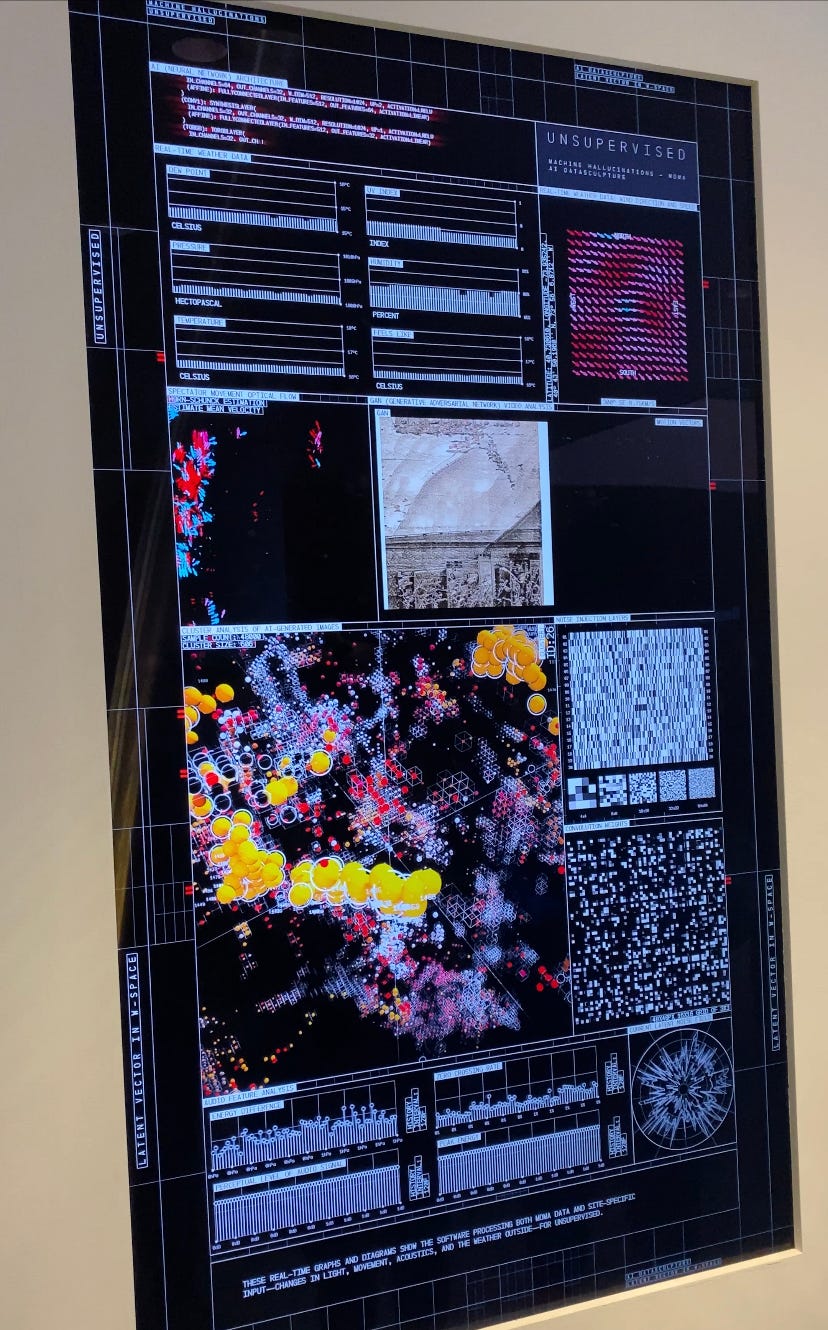

Anadol has an interface screen that shows us the information coming into these visualizations, but there’s no context. There are pieces of code here and there, giving it the feel of an interface from The Matrix, but it’s oriented toward mystification of the AI, rather than clarity. If you aren’t an engineer, you’re not going to “get it.” If you are an engineer, you might be confused about why this looks the way it does.

This, I think, is one of the frustrations I have with Unsupervised. The information screen is really designed to emphasize the complexity of the AI system we are looking at. It’s paired with an epic ambient drone, the type of thing that plays when you’re flying over mountains in an IMAX theater. It feels to me like Anadol wants us to be in awe of this thing, to be overwhelmed by the calculations the machines can make, and by contrast, that humans cannot.

What I see here is purely data analytics, but most of the commentary around me took it differently. They took it as evidence of the impenetrability of AI systems. Anadol’s intention may be to highlight the vastness of calculations, which many works in the 2012-2018 genre associated with math and scale. There’s a sense that math explains this universe, but that we aren’t able to understand it. This logic seems to believe that math is a means of representing the universe in its entirety, even in its spiritual aspects. I’m reminded of Darren Aronofsky’s 1998 film, Pi, in which a numbers theorist, aiming to predict the stock market through the use of a powerful computer, discovers the forbidden name of God.

Some idea that the machine is seeing something, or showing us something, about human creativity always seems to be on the tip of the tongue of these creators, but if there is any insight to be gleaned about what it means to be human, I didn’t see it on that 24 foot screen in Manhattan. But I suspect Anadol does, and isn’t being obscure for cynical reasons. Nonetheless, a lot of more recent work in AI seems to have shifted the lens.

Alternative Models of AI Art

Just up one staircase at the MoMA is a wall-sized print of Anatomy of an AI System, Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s 2018 piece which serves as a systems map of Amazon’s Echo. That piece shows us everything from the mining operations for cobalt and respective pay scales of miners and CEOs, to the ontologies of knowledge frameworks that drive AI developers to frame intelligence the way that they do.

It seems to me that these perspectives of AI are worth thinking of against Anadol’s piece. On the one hand, you have an AI systems that visualizes the MoMA as a closed system: all of art in the archive is stripped of its surrounding context, isolated solely into visual patterns, and then re-represented as a collective whole simply by virtue of having been put into the MoMA’s archive. Questions about who made these artworks, how they were obtained, and why, are absent from Anadol’s piece. Instead, we get information about who is in the building. The art engages with the entire visual history of the MoMA archive, but what we learn about the institution is limited to its humidity and attendance records.

Aside from Crawford and Anadol’s work at the MoMA, “What Models Make Worlds: Critical Imaginaries of AI,” is on at the Ford Foundation Gallery. The artists in that show, they write, “open up the black box for scrutiny, imagining possibilities for feminist, anti-racist, and decolonial AI.” Crawford and the artists at What Models… operate in ways that shine light into these machines, which are forever being touted as too complex and powerful for people to ever engage with. Anadol, I’m afraid, leans so heavily into showing this obfuscating beauty of computation that he only elevates the black box into something Godlike, a metaphor for all things that humans may never know, and, by association, a part of the fabric of cosmic mystery.

We learn very little about artificial intelligence, aside, perhaps, from the idea that it is unknowable to our meagre minds, and that we must, instead, gaze upon its products amongst the hushed awe of ambient drones. The work is beautiful, and for many — particularly in the AI sphere — it is this visual beauty that serves as a checkmark: “creativity is solved!” But Anadol’s piece is also a deeply ideological one, and it asserts — unintentionally, I am sure — a story about AI that makes us passive to it. It’s as if AI is so complex, powerful and inevitable that we can only sit, look, and allow it to surveil us. We’re left staring at the incomprehensibility of the pictures that emerge, with no sense that these are just images in-between the things we humans have already made. It’s a future framed as endlessly lateral, rather than toward something else.

New Organizing Committee Record!

New album is out this week! Go check it out, if you haven’t already.

Shedding a Light on Shadow Prompting

I have a new article up on Tech Policy Press this week, which is about “Shadow Prompting.” GPT4 now changes your DALL-E 3 prompts — but it’s often opaque, and typically undisclosed. I looked into the risks of that as an emerging norm, and some precedents for how we might frame it.

the art of refik anadol = glorified screensavers.

For Refik Anadol, the manipulation process to which he subjects the data he uses in his pieces is so amazing that for him, that is enough.

Anadol's art uses very advanced technologies to create very primitive results, which certainly a cell phone screen is perfect for viewing.