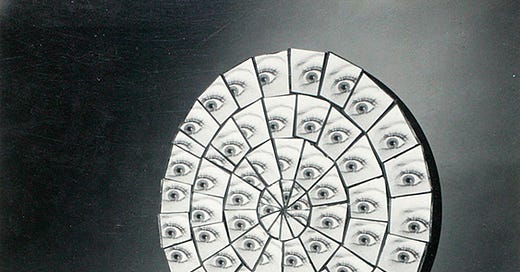

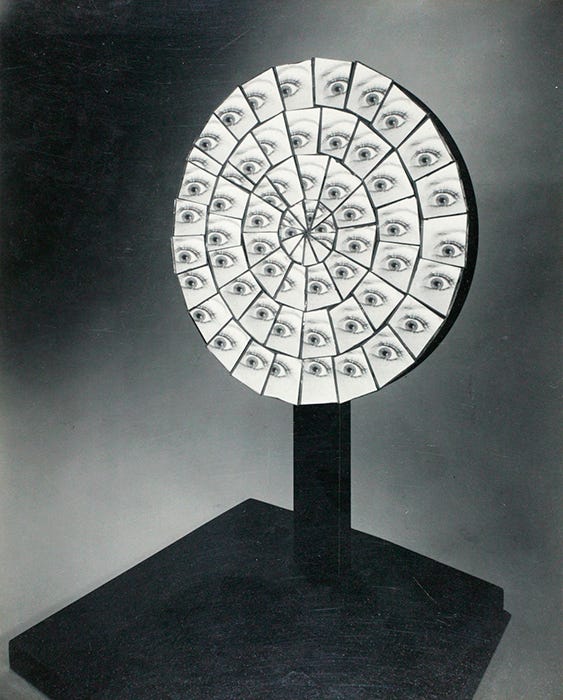

I came across this image last week and scratched my head wondering which Dadaist was responsible. Turns out it’s the work of the photographer Berenice Abbott, who on top of documenting life in New York City in the ‘30s was also in the business of illustrating science text books. In the ‘60s her work moved into physics.

“The function of the artist is needed here, as well as the function of the recorder. The artist through history has been the spokesman and conservator of human and spiritual energies and ideas. Today science needs its voice. It needs the vivification of the visual image, the warm human quality of imagination added to its austere and stern disciplines. It needs to speak to the people in terms they will understand. They can understand photography preeminently.” (From Abbot, in a 1939 letter).

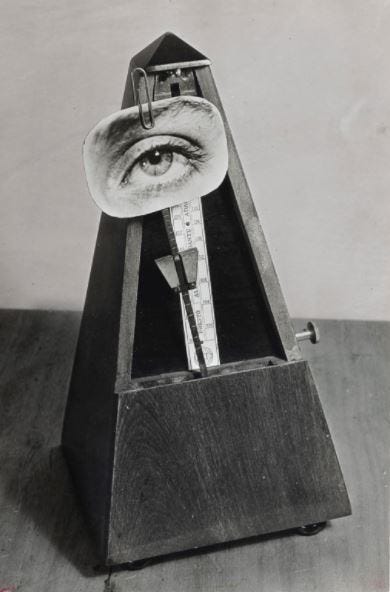

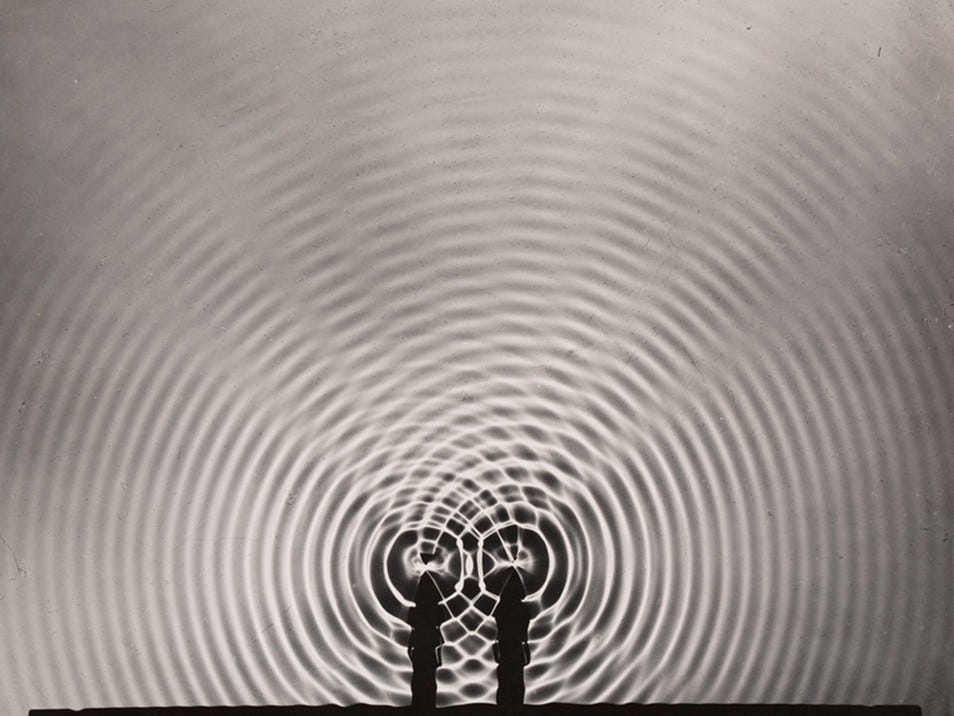

The work above was created while Abbot was with the Physical Science Study Committee at MIT, aimed at better representing scientific concepts in education. Abbot had been a studio assistant for the (problematic) Dadaist, Man Ray, in the 1920s. He’d famously worked with X-Ray photography and various kind of film exposure, and also made at least one eye sculpture (though I prefer Abbott’s).

But Abbott was less interested in using physics to make compelling work, and more interesting in using work to make physics compelling. This wasn’t an everyday practice at the time. Much of the scientific community — in a bit of conservatism that lingers today — feared that public “engagement” in science was inherently corrupting. Science should be “disinterested” and that, one assumes, required a disinterest in science. In 1938, Robert Merton, an American scientist, argued that Nazi science was the result of populist interference in the rational work of science:

“In [the German] case, the sentiments of national and racial purity have prevailed over utilitarian rationality. … The general tone of anti-intellectualism, with its depreciation of the theorist and its glorification of the man-of-action, may have long-run rather than immediate bearing on upon the place of science in Germany.” (1938, p. 256)

It was Jewish refugees, fleeing Nazi terrors and repatriating to the United States, who started the American culture move toward science as a source of awe and wonder. The idea of scientific independence from the “public” had driven research into the hands of the state, creating the conditions Merton describes.

But Abbott had a sense of this already. So when MIT received funding to expand American science education — the result of Cold War Sputnik hysteria — it was a natural fit.

Other products of this lab were, on the whole, a bit dull, reflecting a very minor break from chalk-and-talk pedagogy, though delivered in clear, jargon-free and accessible language. But even they had moments of strange, surrealist flare, like this image of legs filmed underwater, which soon starts kicking to show the effect of motion on perception.

One other notable contribution from Abbott is that her work as an artist contributed to the understanding of the physics fluid and light amongst scientists as well as the public, which I feel is an overlooked contribution. I often feel that science communication is treated as PR for scientists, rather than a form of research aimed at extending the understanding, application and extension of knowledge. Perhaps the breakthroughs that came from the high school students exposed to Abbott’s brilliant renditions of these concepts can be said to be standing on her shoulders, too.

Cybernetic Ephemera

Found in a 1976 issue of SCCS Interface Age:

As a result of looking into this, I found a miraculous project on GitHub that converted the software used to make the “Unplayed by Human Hands” album into MIDI files.

Things I’m Reading This Week

Why aren’t people good at thinking just for fun?

Erin C. Westgate, Timothy D. Wilson, Nicholas R. Buttrick, Rémy A. Furrer, Daniel T. Gilbert. What makes thinking for pleasure pleasurable? Emotion, 2021; DOI: 10.1037/emo0000941

“Daydreaming can be an antidote to boredom, which Westgate's work has shown can induce people to bully, troll and show sadistic behavior. In one experiment, participants opted to kill bugs with a coffee grinder to alleviate their ennui. (The bugs weren't actually hurt, but the participants didn't know that.) In another study, 67% of men and 25% of women preferred to give themselves an electric shock than be alone with their thoughts.”

Decolonizing Electronic Music Starts with its Software

Tom Faber, Pitchfork

Great read on how electronic music software defaults to specific, Western ideas of musicality — and not even all of those. Khyam Allami has built a set of electronic music tools intended to help electronic musicians from non-Western cultures reproduce the music in their heads. It can also help people from all cultures think about hyperlocal (as in, personal, experimental) systems of music making.

AI Generates “Personally Attractive” Images

Michiel Spape, Keith Davis, Lauri Kangassalo, Niklas Ravaja, Zania Sovijarvi-Spape, Tuukka Ruotsalo. Brain-computer interface for generating personally attractive images. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 2021; 1 DOI: 10.1109/TAFFC.2021.3059043

The study is intended to help individuals understand their own biases, but I’m personally interested in this in the short term as a field for manipulation and, long term, imagining some terrible form of dystopian entertainment, harvested straight from the patterns of unacknowledged neurons.

What I’m Listening to This Week

The London-based artspace brings its podcast back after a short hiatus, and it’s good news. It has been a generous mix of thinking about technology, art, and society from a very specific perspective.

The Kicker

Go listen to the surface of Mars — if it were reproduced as the surface of a vinyl record.

Thanks for subscribing! As always, if you found any tidbits useful, please share it wherever you please!