The Future As Imagined

"Time is Out of Joint"

The foundation of generative AI is data from the past. This raises a question: how does the past generate a future? The human answer to this is embedded in ideologies. We arrive at a set of values, and engage in social arrangements that reflect those values. We sustain these beliefs by confirming those values through the films we watch, the media we consume, the conversations we have and who have them with.

One way we confirm those values is through stories. One kind of story is particularly good at linking values to future worlds, and that is science fiction. Science Fiction was such a powerful ideological tool that the USSR banned it, just as it once banned cybernetics. Both bans were eventually lifted, and Soviet science fiction became another tool of the ideological apparatus.

Lately I have been investigating Algorithmic Hauntology. It’s drawn from Mark Fisher’s essay on Sonic Hauntology, which explored the musical forms shaped by retro-futurism: a musical genre in which the past’s imaginations of the future were portrayed as lost possibilities, a present world haunted by ideological visions that never came to be.

The musical representations of this logic were ethereal and uncanny. The Caretaker, an act named in Fisher’s essay, takes musical recordings from the 1930s and 1940s and slows them down: scratches and hiss are preserved; the spaces between notes are filled in with echo and reverb.

This is a music of archives, an act of re-engagement — re-generation — of the musical archive. The relationship between our position in time and the time of the original recording is applied as a layer of distance that allows the listener to re-inscribe a new layer of meaning and interpretation.

Talking to Mark Sullivan about this work this week, I was pointed to a 1980 recording of a piece by Charles Dodge, called “Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental.” Here, we see something akin to sonic hauntology, but it is also touching on algorithmic hauntology. The relationship between the past and present is still a mediating form, as it involves a computerized restoration of a recording of Enrico Caruso from 1907. The computer was designed to analyze the notes and reproduce them using a digital voice.

As the title of the piece implies, there is a gap between past and present — as in Sonic Hauntography — but also a gap between the present (a live piano) and the digital interpretation of that present (the voice reacts to the piano) and the past (the voice responds to recordings).

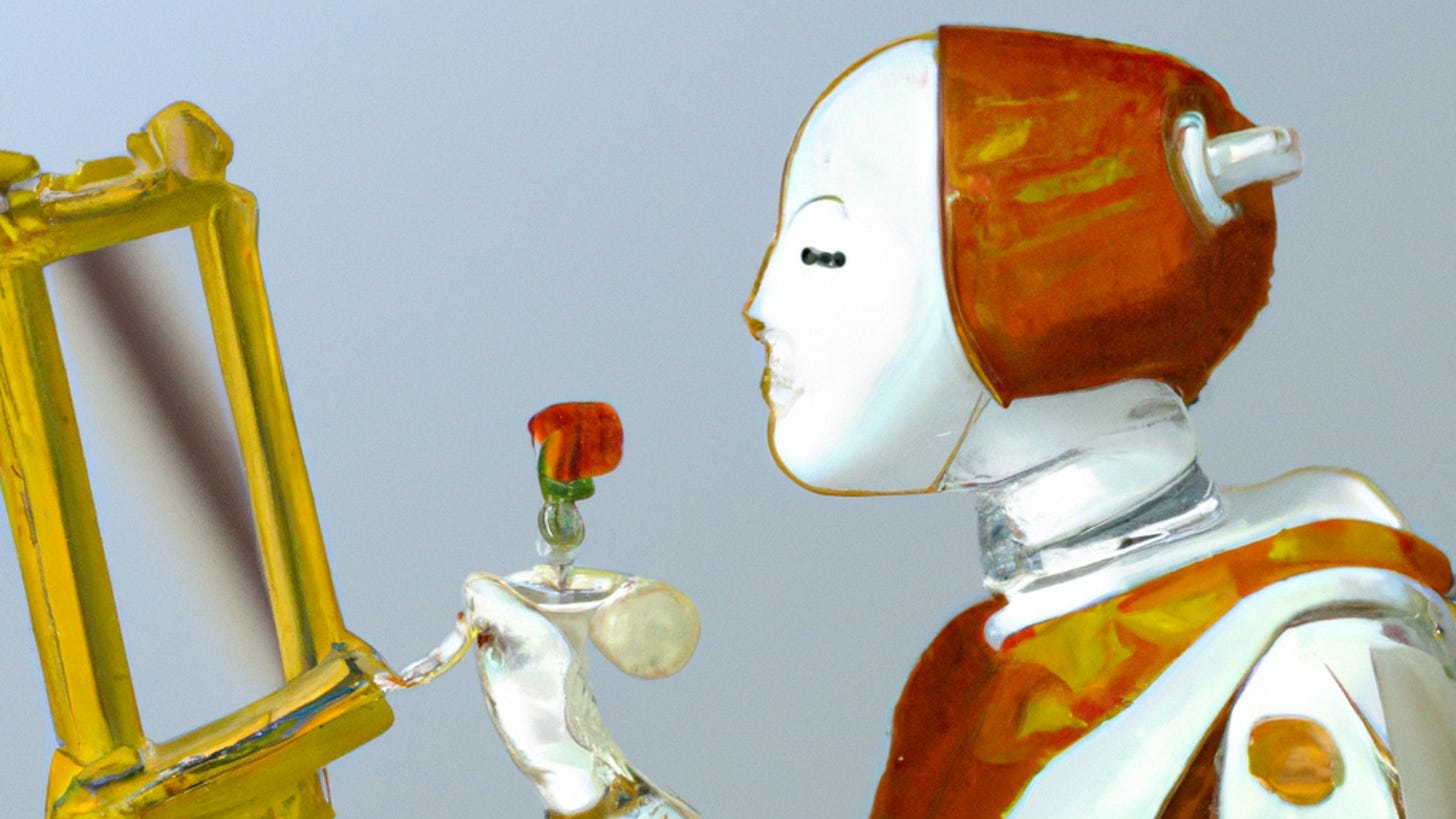

I was showing a series of images, generated by Midjourney, in which I prompted images depicting the future as imagined by the past.

Roland Meyer — who writes some brilliant threads about Midjourney and Diffusion Models — has talked about the ways these system describe the past:

For AI image synthesis, historical dates usually do not denote singular events but, to quote Fredric Jameson, rather a generic “pastness”: visual styles and atmospheres replace any concrete and specific past. In Platform Realism, history dissolves into aesthetic “vibes.”

This connected to the images of the future: the future itself, as represented by Midjourney, did not change all that much. Cylindrical objects still hovered in air, filled with either helium or strange propulsion systems. People looked out at cityscapes. Moons have multiplied.

It’s an empty aesthetic gesture, of course: Midjourney has one particular concept of the future, and simply applies the stylistic conventions of historical archives to color in the lines of that imaginary future world with artifacts of the decades in the prompt. There is only one future in the Midjourney concept space, everything else is decoration.

When I engage with Aesthetic Generative AI, I am looking for what it says about the structures of larger information-organizing structures. The gaps between the present and the past are one problem with these structures: a census reflecting a city’s past cannot “predict” its future; but it will try. Those predictions have a gap in which a haunting materializes: redlining practices segregating cities, for example, linger in those predictions; the people who did not live in a neighborhood cannot be counted, but their absence shapes the prediction.

The algorithmic gap, or the uncanny valley, is the gap between the predicted present and the predicted future. Algorithmic systems do not operate through experience, but by expectation: models of the present. We should be deeply skeptical of asking ChatGPT about our current world; likewise, we should be skeptical of its guesses about the future. That may be obvious, but the same skepticism matters for data of all kinds. Algorithmic harms result from enforcing past predictions on present populations.

A new paper from Richard Carter coins the phrase “Critical Image Synthesis” and makes some great comments on the roles of artists (myself included). Critical Image Synthesis can model algorithmic resistance by invoking a particular relationship to AI and its influence. This goes beyond creating new aesthetics. Critical AI Synthesis can confront mystification, advocate for just systems, empower critical thinking, and demand better AI.

The paper asks “whether … AI image synthesisers may still afford a means of contributing to their own analysis and reframing. That is, whether they can be deployed in ways that are generative of future potentials of critically informed thought and action, rather than being treatable only as negative objects of scholarly excavation and critique.”

It’s a contrast to many (not all) generative AI artists, who seem to feel obligated to defend unethical data practices, expand AI hype, and shy away from the tensions, ambiguity, contradiction, and complexity that comes from working with these systems. Alternatively, artists can hone their craft through engagement with the challenges these tools create: we can raise critical literacy about algorithmic harms, but also challenge ideologies of the future that they are destined to reinforce.

Algorithmic Hauntology takes place in the distances between the past and present, alongside the gaps between algorithmic predictions of the present and future. In these spaces, artists can resist or expose that haunting: engage in interventions, circumvents and negotiations that reclaim and recenter human agency and creativity. It is a meta-analysis of the systems we use, and a repurposing of their affordances toward our desires, our imagination, and our futures.

Things I Am Doing This Week

New York

On September 13, I will be at the Creative Commons Symposium in NYC, “Generative AI & the Creativity Cycle,” speaking on a panel about archives as a resource for generative artists. You can find more information on their website or through the button below.

New York

On September 14, I will be at the New Museum in NYC speaking to the New Inc CAMP cohort and alumni to offer a first glimpse of our “Playing with Tensions: AI for Storytelling” report co-written with AIxDesign over the course of the Story&Code program, where creative technologists and professional animators were paired together to craft new workflows with AI.

It’s a closed-door event, but you can find out more about the program through the button below. AND, you can find details about a public event in Amsterdam in October underneath it (Perhaps I will see you virtually!)

Pittsburgh

From Oct 6-8 I will be at Carnegie Mellon University for RSD12, and will be part of a conversation in the “Colloquies for Transgenerational Collaboration” track organized by Paul Pangaro as part of the ongoing #NewMacy events with the American Society for Cybernetics and the global RSD 12 conference.

I’ll also be presenting a new paper, How to Read an AI Image Generation System, online on October 9, which is essentially a whole ongoing parallel conference. RSD12 is taking place all over the world this year, do check it out if you are interested in Systems Thinking and Design! More about RSD12 below.