The Latent Space Myth

Is Gen AI a Perpetual Motion Machine?

“Oh ye seekers after perpetual motion, how many vain chimeras have you pursued?

Go and take your place with the alchemists.” — Leonardo da Vinci, 1494

I was sleeping in a hotel on Roosevelt Island. The UN building was just across the East River, visible beyond the ruins of a 19th-century smallpox hospital. Sam Altman had just announced that o1 was heralding a new era in deep learning, no doubt timed to hit the diplomats assembling at the UN for the General Assembly taking place some short distance away.

In “The Intelligence Age,” Altman writes:

I believe the future is going to be so bright that no one can do it justice by trying to write about it now; a defining characteristic of the Intelligence Age will be massive prosperity. Although it will happen incrementally, astounding triumphs – fixing the climate, establishing a space colony, and the discovery of all of physics – will eventually become commonplace. With nearly-limitless intelligence and abundant energy – the ability to generate great ideas, and the ability to make them happen – we can do quite a lot.

That morning, I woke up from a dream, laughing. My exhausted body was still somewhere between the time zones of Spain and San Francisco, and I was dreaming of sleep. I had fallen asleep in the dream but was woken up to the news of some unnamed technological breakthrough. I credited myself with this accomplishment: I had advanced this scientific breakthrough and hastened it by dozing off—sleeping my way into technological progress.

I woke up in real life, turned to my phone — the source of most of my exhaustion — and found this post by Tante on the ways we talk about as-yet-unrealized technological progress. That is, the hype we mistake as evidence when we talk about tech:

We are constantly asked to keep talking about things as potential. To judge things based on promises of what they might do that go way beyond the actual realities of the thing. Like OpenAI and others can’t make any money with their machine learning models. But their text and image generators might bring a 10% GDP increase as Meta’s open letter claims? You sure about that? Sounds like that requires a lot of magic thinking between 1) “OpenAI builds stochastic parrots” and 3) “GDP goes up by 10%”. How exactly is 2) shaped in this chain of reasoning and does it actually exist? … In the tech discourse we need to stop thinking and talking about things that do not exist.

I’m reminded of something else—a bridge connecting the “AI art theory” discourse with the “AI hype discourse.” This is the myth of the latent space.

The latent space terminology in AI image generation started as a way to explain the distribution of sample points within a model or, more simply, the information within a model that could be accessed to complete its task. Somewhere along the line, the AI boosters started to talk as if every possible permutation of a jpeg, and therefore every possible image, had already been achieved within the vector space of a diffusion model with enough data— or that a large enough LLM has already written every possible page.

The myth of the latent space treats potential outputs of a system as a map of things that are already there, rather than just a spatial metaphor. Instead, “latent space” has come to suggest that there is a map of every possible image inside it rather than the possibility of producing every possible image within the model.

In this imprecise redefinition of latent space, it’s all already made—we just have to find it. So prompting becomes a metaphor for diving, pulling up what David Lynch calls the “big fish,” as if the model contains every permutation of the world, just waiting for us deep below the sea.

The latent space externalizes these ideas: rather than diving into ourselves, we dive into a model in search of ideas. However, these models are, in fact, highly constrained relative to actual possibility. The world can create all kinds of things beyond the confines of the model, and people can dream of all sorts of ideas that the model would never predict could be written.

And that’s the conflict at the heart of gen AI. It’s not an age of “intelligence” per se. What Altman and his AI community call “intelligence” is actually “noise,” or more specifically, the algorithmically mediated tension between noise and order. The tension between randomness and constraint creates the illusion of liveliness, creativity, and thinking in the products of Gen AI. The difference is self-awareness: a presence in the organization of our thinking. It isn’t always there with us humans, but it’s never there in machines.

Philosophically, this gets to the heart of something deep within the AI discourse. Are all possible “things that exist” already predicted and laying dormant within a hypothetical “latent space” of noise? Potentially. Is filtering the noise out of the universe into every possible shape the best way to make things? Doubtful. Altman writes:

Humanity discovered an algorithm that could really, truly learn any distribution of data (or really, the underlying “rules” that produce any distribution of data). To a shocking degree of precision, the more compute and data available, the better it gets at helping people solve hard problems. I find that no matter how much time I spend thinking about this, I can never really internalize how consequential it is.

This is a philosophical position — it points to a belief that every problem is already solved and that the solutions are just waiting for us to build the machine to get to them. Build this one fishing machine, industrialize the hook, use as much bait as you can, and you will catch all possible fish at once. A machine to build all possible machines. But this is not a way reasonable people describe a technology. It is how people engage in thought experiments to discuss a hypothetical technology.

Specifically, this is the hypothetical perpetual motion machine of the first kind: one that produces work without the input of energy. But the energy here is not the energy of heat, fuel, or physics, which AI certainly makes use of. The metaphor shifts: it’s information — data, which is not knowledge — and the flow of data through a system to produce more data. I am not saying that data and energy share similar properties, only that the myth seems to be about the same: that we can go to sleep, and the machine can think up a better world. We can find solutions in the haystack of combinatorial language tokens rather than build infrastructures to invent them.

If you believe this, then a very different set of priorities emerges, one that makes increasingly less sense to those of us who don’t.

A lot of those priorities were on display at a recent convening by Meta on open LLMs. I was invited to a small gathering of folks from the Middle East, Turkey, and Africa that Meta had convened to discuss the ethics of open-source AI with Yann LeCun, Facebook’s vice president and chief AI scientist, in conjunction with the UN General Assembly.

I’ll share more about that on Thursday — in a bid to reduce the length of these newsletters, I’m experimenting with making them shorter and more “episodic” from week to week. Let me know what you think — see you in your inbox Thursday.

A quick note

Are you a regular reader of this newsletter? If so, please consider subscribing or upgrading to a paid subscription. This is an unfunded operation; every dollar helps convince me to keep it up. Thanks!

Things I am Doing Next Week

In Person: Unsound Festival, Kraków! (Oct. 2 & 3)

This week I’ll be in Kraków, Poland for the Unsound Festival! Starting with an experimental “panel discussion” on October 2 (1:30pm) alongside 0xSalon’s Wassim Alsindi and Alessandro Longo, percussionist/composer Valentina Magaletti and Leyland Kirby aka The Caretaker. On October 3 (3pm) I’ll present a live video-lecture-performance talk, “The Age of Noise.” Both events are at the Museum of Kraków. Join us! More info at unsound.pl.

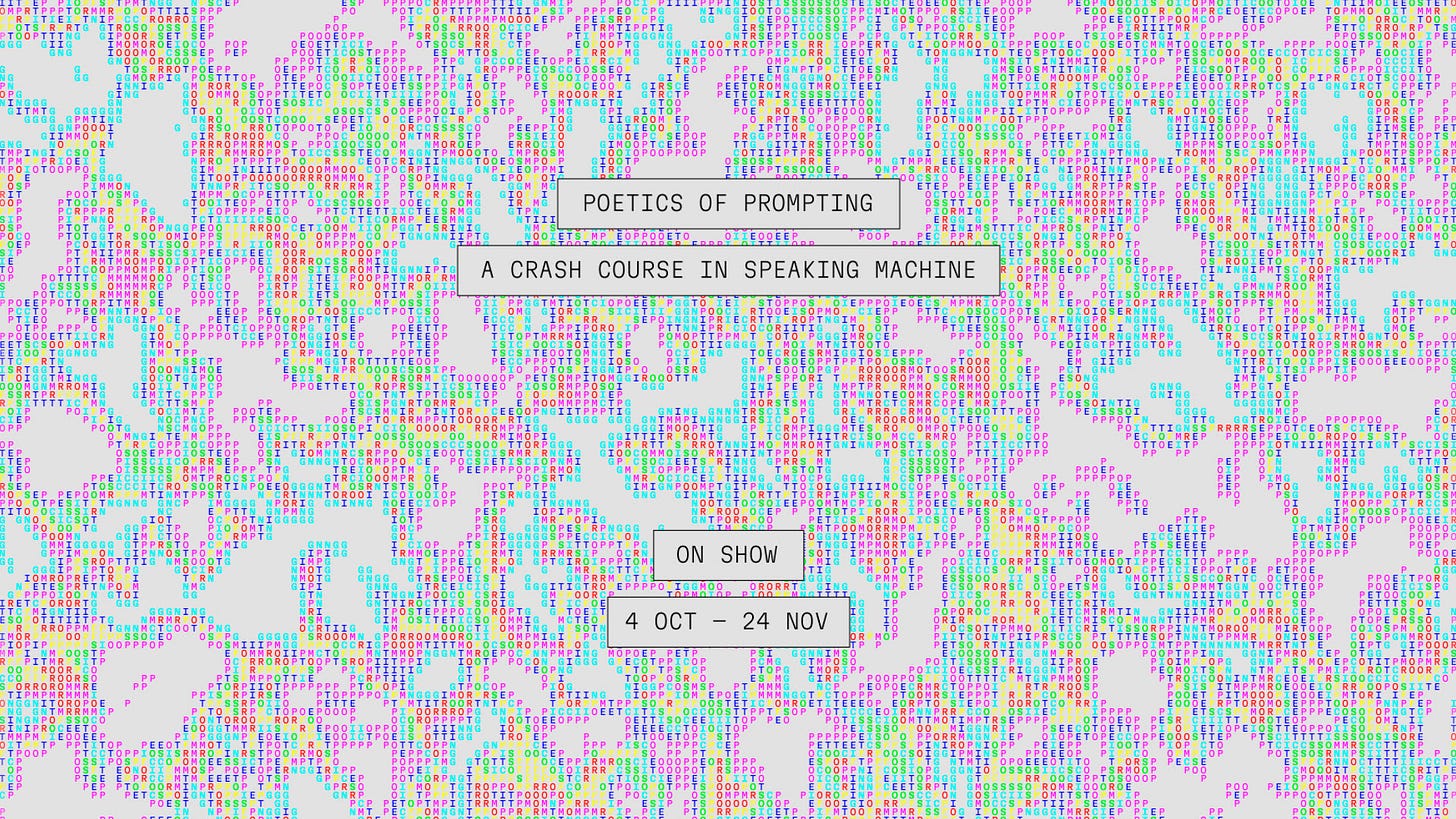

Exhibition: Poetics of Prompting, Eindhoven!

Poetics of Prompting brings together 21 artists and designers curated by The Hmm collective to explore the languages of the prompt from different perspectives and experiment in multiple ways with AI. In their work, machines’ abilities and human creativity merge. Through new and existing works, interactive projects, and a public program filled with talks, workshops and film screenings, this exhibition explores the critical, playful and experimental relationships between humans and their AI tools.

The exhibition features work by Morehshin Allahyari, Shumon Basar & Y7, Ren Loren Britton, Sarah Ciston, Mariana Fernández Mora, Radical Data, Yacht, Kira Xonorika, Kyle McDonald & Lauren McCarthy, Metahaven, Simone C Niquille, Sebastian Pardo & Riel Roch-Decter, Katarina Petrovic, Eryk Salvaggio, Sebastian Schmieg, Sasha Stiles, Paul Trillo, Richard Vijgen, Alan Warburton, and The Hmm & AIxDesign.