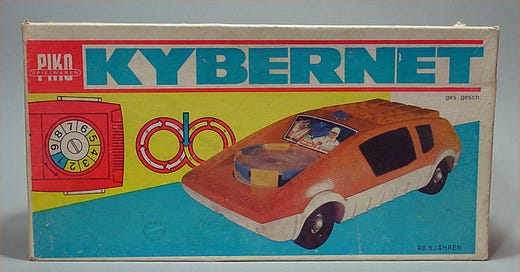

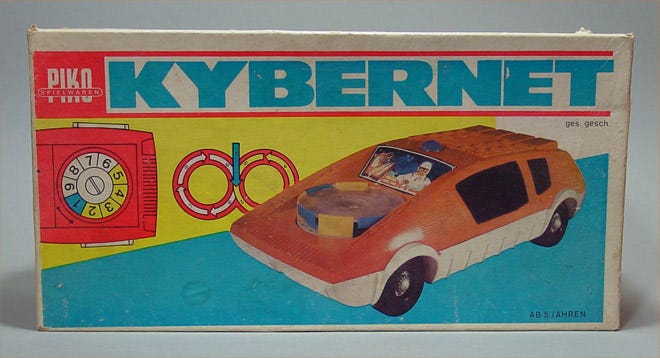

I came across the Piko Kybernet thanks to Zentrum für Netzkunst, who is putting together a series of papers and exhibitions about the relationship between East German socialism and the science of cybernetics. They linked to an article, in German, about the Media Archeology archive of Humboldt University, which has a copy of the car and its packaging. It explains why:

“At first glance, it may not be clear why academic media studies need such a thing. The reason is simple. The Kybernet is an example of a toy car with which the society of the time wanted to introduce children to the idea of cybernetics (hence the name) and the basic requirements of the computer from an early age.”

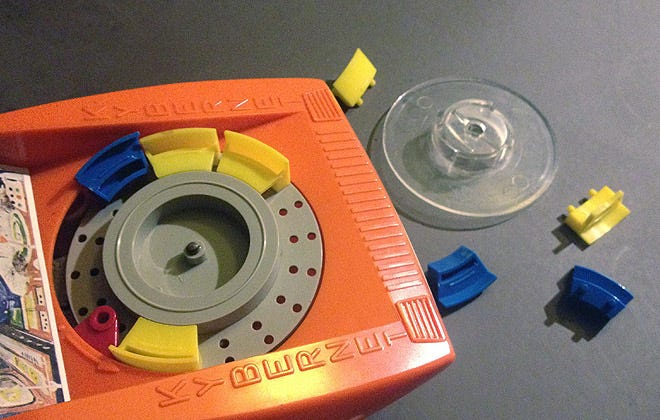

The Kybernet is an early imagining of a self-driving car, with the course programmable through little plastic pieces inserted into the disk on the hood.

There was an ideology in socialist Germany that toys and education could shape the public’s taste for objects which inspired imagination, a sense of beauty, and solid craftsmanship. It also expressly linked the play of children to their future careers.

This was pitched against the idea of cheap, mass-produced “kitsch,” which it identified with capitalism. Because the state controlled access to goods, Shannon Nagy writes in The Power of Play, it was able to regulate goods which it believed could injure the “character” of people, rather than just their health or bodies the way regulation might in the West. The maxim was, “If only good is produced, nothing bad can be sold.” There was even a short-lived Ministry of Toys in the 1950s.

But imagination had a weird history in the Soviet Union under Stalin. Cybernetics was mostly banned. In East Germany, Utopianism was a fascist project, and imagining the future was perilously close to imagining Utopias. Strict rules were imposed on science fiction films to ensure they remained rational, and did not allow viewers to compare their reality to one which did not exist.

That ended, of course, by the time a self-driving computer car was introduced as a toy for children.

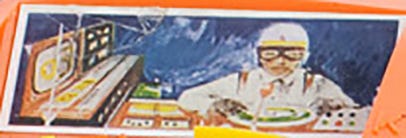

The “story” this object tells is that of a race car driver, speeding along while placing objects into a computer to set his course. The fantasy is that speed and movement can be powered by the child’s knowledge of computer programming. The plastic represents a deliberate kind of modern-ness for the period, amidst a minor design backlash at the time against plastic as a mass-produced material.

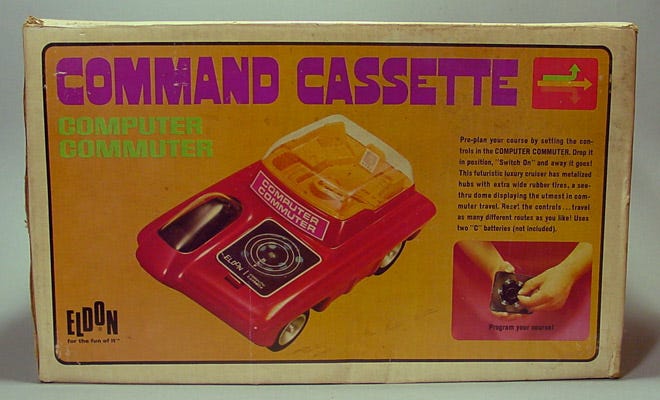

I would love to know the history of this sticker, affixed to the front window of the car, and all of the discussions that went into it. One person, alone, in a car? For all of the ideology, it’s worth noting that a Japanese toy company produced a toy exactly like this one in 1969, a luxurious imagining of capitalist mass-transit which was sold in the US as “The Command Cassette Computer Commuter.”

This one has a small plastic disk that you can position in alignment with a series of small holes on the hood. The path on the disk sets the path of the car. Nonetheless, there is still a driver’s seat, though the packaging tells the story of a living room, complete with a “hi-fi and TV control unit.” This imagination of the autonomous vehicle tells a story of “individualist mass transit” which is still embedded into the way we imagine the future of autonomous vehicles today.

It makes initial sense that the capitalist imagination is a private version of public transport. But it’s counter-intuitive that the socialist fantasy would be an individual racecar driver, wasting gasoline for sport.

But autonomous systems of speed, motion, and control were deeply engrained into the history of Soviet Cybernetics. The Soviet version of Futurists - the Prognostik - were loyal to the cause, writes Sonja Fritzsche in her history of science fiction in East Germany. They advocated for “dreaming ahead” to socialist futures in order to anticipate missteps. While Cybernetics was viewed with suspicion under Stalin — “production without workers” stripped the ideology of all its power — it began to emerge more cautiously with regime change.

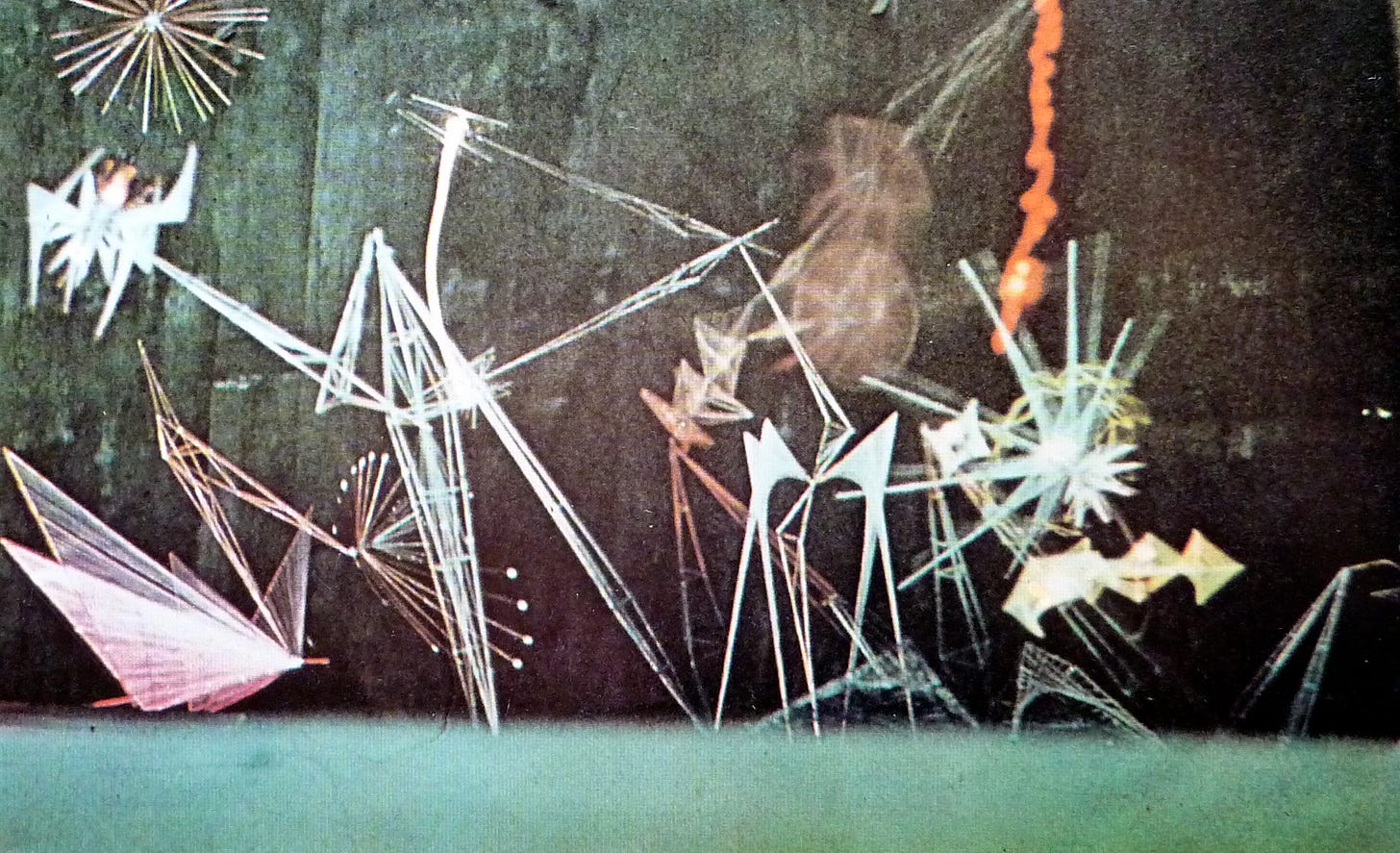

By 1967, it was fully embraced. The art group Dvizhenie (more) created a cybernetic artwork — “Cybertheater” — in Leningrad to mark “50 Years of Revolution.” It was a kinetic piece that responded to those who passed through it with strange sounds, lights, and steam, an imagining of a distant planet or a distant future. Here’s a picture, which I can’t quite comprehend, but it looks amazing.

The Prognostik view, which was eight years old by the time the previously subversive science of cybernetics was accepted by these Soviet regimes, saw "the worker as the source of participatory inspiration in collective prognosticating, planning, decision-making, and managing" with the aid of cybernetic systems. Democratic participation in the Soviet management system was a problem cybernetics briefly believed it could solve (see Project CyberSyn, the Chilean socialist-democratic cybernetic experiment which ended in a coup a year before the car was on shelves in East Berlin).

So that individual alone in the race car might not be in a high-speed escape away from his social obligations, but racing toward them. He is the driver not only of his own car, but driving the management of information management into the future of work.

Things I’m Doing This Week

I was invited to create a series of visualizations and soundscapes for Ellen Broad’s keynote talk imagining AI from an Australian perspective.

This is a still from the film, which runs 15 minutes. It deals with the Australian Orb Weaver spider, which Ellen notes takes down its web at the end of the night, so as not to ensnare other animals or insects when it doesn’t need to. Thinking about Australian AI is not about centering a national identity or history, but about learning from the unique creatures that maintain Australia’s complex ecosystem of plants, birds, spiders, and many variants of kangaroo.

It’s this Tuesday in Melbourne, for Melbourne Design Week, if you are interested to attend, and it will include Ellen in conversation with Tyson Yunkaporta and Fiona Milne.

Things I’m Reading This Week

A View of the Future of Our Data

Matt Prewitt

An article explaining data cooperatives sets itself in the future in order to explain complex ideas about the present. It’s a policy paper and it’s science fiction.

It is important to emphasize that “your data” and “my data” do not exist as distinct things. My address is my father’s son’s address, and my genes are the genes of my cousins. My deepest desires are also the desires of my friends, not just because we have common backgrounds, but because we communicate and form our desires together.

New World Order: For Planetary Governance

Benjamin Bratton

A dense but provocative essay examining and challenging core orthodoxies of agency, algorithms, and the consequences of what is, at a global scale, anarchy between national actors. Bratton reframes “governance” in cybernetic terms: self-awareness, and self-organization, of our own species in order to save itself.

Societies must have the ability to not simply produce and consume mindlessly but to deliberately compose themselves. Planless emergence may be the background force of evolution, but deliberation and deliberateness have themselves emerged and must be re-embraced as the basis of collective agency. … If we’re going to construct the basis of a twenty-second century worth living through, our capacity for self-composition must be the subject of our most intense imagination and reason.

The Kicker

How Generative Music Works by Tero Parviainen (I linked to another project of his last week!) is an astounding introduction not only to how a particular genre of music is made, but how feedback loops and coincidences inform the creation of that music. In one sense, it’s the best introduction to cybernetics I’ve ever seen, on another, it’s just tons of fun.

As always, feel free to share this post anywhere you see fit. Sign up if you dig it, it means a lot!