Posting will be sporadic this month as I am in motion between a few different places and states of mind. This post expands on a response I recently sent to a discussion on the netbehavior mailing list.

The discussion list, or listserv, is a bit unfashionable in our age of social media. It's email from strangers who think about similar things. There are no likes or shares, just responses. Responses take time. Oddly, I am more comfortable if nobody responds to a multiple-paragraph e-mail than I am when a ten-word Tweet goes ignored.

I was raised on the flow of discussion lists, where people had time to read and write, rather than like and share. One of my first forays into the Web was called 7-11, which was for net-art what the Cabaret Voltaire was for dada. 7-11 was frustrating. It was anonymous and full of spam. It’s only home on the Web was disguised at a convenience store. It often seemed like a group of people trying their damndest to get each other to unsubscribe, or break the list.

I had a project where people elsewhere on the Web could pose a question to Abraham Lincoln. Those questions redirected to 7-11. Keiko Suzuki, the fictional moderator of the list, was actually a composite identity. Queries went to 7-11, and people could respond via another text box to send emails from her account. She even conducted interviews in this way. It has been written about in hindsight by a variety of artists who are now “canonical” in the development of net.art, but it doesn’t seem like any archive has survived.

From there, I started a foray into online communication with strangers via e-mail discussion lists.

There's a discussion that pops up in these discussion lists often. It's about why some people post and other people don’t, and where responsibility for a community rests. I don’t post to the lists I read very often. There is the issue of time: I know I don't have time to be thoughtful. There's also a sense of respecting the conversation. Posting feels interruptive of other conversations, including the conversation that feels like list-silence. Posting — when I post — feels performed rather than generous. Again, this is my feeling about the act — it never crosses my mind that anyone else who posts is performing. I always see it as generous.

Maybe it’s useful to frame this as an intellectual exercise: “what was the Listserv?” — though I hate to suggest that the Listserv is dead. Listserv is a registered trademark, though widely abused, and capitalized by autocorrect. Here I use it to refer to a range of software systems designed for automated, e-mail based discussion lists.

The practice itself seems to date to the 1970s, where lists were manually distributed by moderators. With the Web came automation. One of the earliest, LINKFAIL, was a listserv dedicated to announcing internet failures. LINKFAIL could create so much traffic that it would speed up failures it was reporting. (LINKFAIL, also, seems not to be archived).

The organization of mailing lists and responses draws from Usenet Newsgroups. These organized conversations (data) from various places and times into one place. This is where we got “threads.” The original post is usually at the top, and responses follow below it according to time. This mirrors a system already known to many users of the time: academics.

Listserv threading, emerging from academic communities, follows the structure of publication, or debates. Like systems of academic publication, which are built on anonymous peer review, the "thread" can encourages responses ranging from praise to constructive criticism to rejection and abuse. These mirrors all kinds of toxic side-effects of academic communication, including imposter syndrome. There can be a sense that your contribution to a space has to be “earned.”

On the other hand, a thread is designed to be collaborative. It’s created by response, a feedback loop of interaction. A post without response disappears. A post with a reply lives, until it doesn’t. The “thread” runs through the content and form, tying it together until it “runs out of steam” or gets “derailed.” Tellingly the metaphors move from knitting yarn to the brutal industrial-era metaphor of a train either crashing or losing energy: we never say that the thread has been sewn, the fabric patched, or the quilt completed. Conversation is always in a possible state of revival, never finished unless it fails.

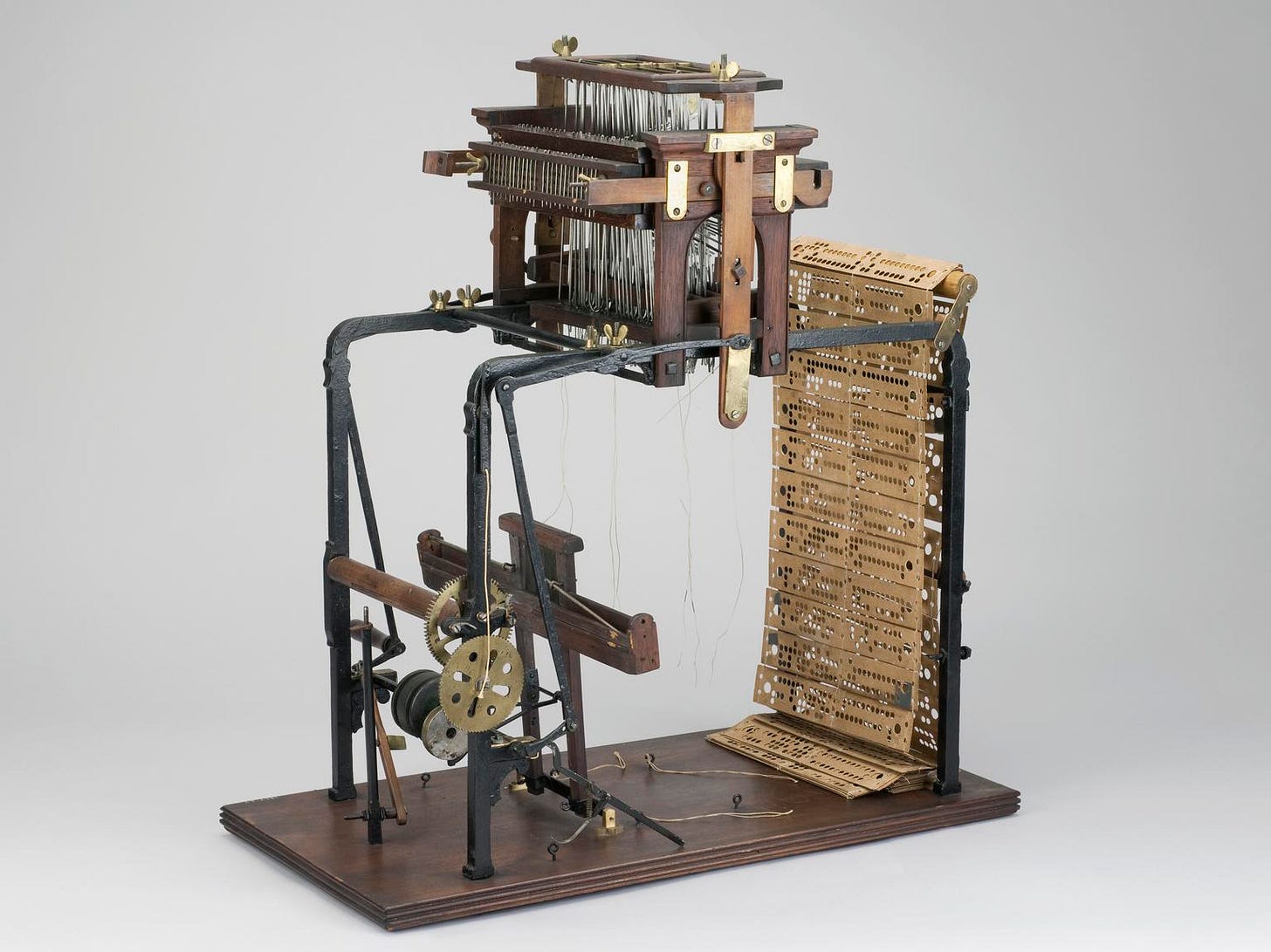

The use of “thread” to describe this structure may be a tip of the hat to Ada Lovelace and the Jacquard Loom, a device which could automate the sewing of patterns into fabric. Instructions for those looms are consider one of the earliest forms of computing.

Another (not mutually exclusive) explanation seems to come from a 1967 paper, where Jerry Saltzer at MIT used“thread” to describe how a sequence of steps should be controlled when a computer executes a program:

Dennis and Van Horn have used the words "locus of control within an instruction sequence" to describe a process; the alternative term "thread" (suggested by V. Vyssotsky) is suggestive of the abstract concept embodied in the term "process." (p.20).

On Twitter, the “thread” is a mechanism designed for the opposite of feedback. You “thread” a series of linked posts, forming an uninterrupted soliloquy. Nobody has to interact before you form and post the next thought. Less salon, more soapbox. (Notably, I write this bit several paragraphs in).

My relationship to the Twitter soliloquy, with its torrent of promotion and opinion and argument, may have tainted the act of sharing my own art and ideas on discussion lists. People there are not signed up for “me,” the way they might be on Twitter or Instagram. Posting has come to collect an association with likes, clicks and other affordances of today’s digital validation. It’s a system which tends to encourage imposter syndrome through design. Participation demands the assertion of “a contribution,” but what is a contribution but the sharing of an idea — a train sent from the station to see if it can sew a quilt?

But a Listserv can also be a respite from the “follow”, a space to encounter and be encountered rather than an extension of ourselves. I suspect it’s helpful for us all to confirm that from time to time: the mailing list is created collaboratively, it requires response and feedback to survive, and it’s up to us to encourage overcoming the legacy of its design by balancing hard against the biases it inherits.

Things I am Reading This Week

###

Why Gregory Bateson Matters

Ted Gioia

A look at the work of cyberneticist (ecologist-psychoanalyst-technologist) Gregory Bateson, with an eye toward what it means to be “counterculture” in today’s world.

In the old days, a company might spend decades developing production capacity and distribution networks in different parts of the globe, but nowadays the fastest-growing business models can reach everywhere almost immediately. To describe this in Bateson’s terms, the digital age is built on the backs of runaway systems. And in an uncanny, disturbing way, even our day-to-day lives away from screens and digital interfaces seem to mimic this tendency, riding a wave of escalating trends with no feedback loop to keep them in check.

#

Why Do AI-generated Portraits Fail at Realism?

Filippo Lorenzin

On relationships between AI art and kitsch. Lorenzin writes about how important context is for the way we view art, and how AI fails so catastrophically at capturing what is exceptional when we train it to strive for the general:

If artists made portraits in that Realist style now, their approach would read as kitsch. So says the Italian art historian Gillo Dorfles in the book Kitsch. The World of Bad Taste: “The people who made these camouflages of authentic avant-garde art have isolated one single aspect of the artistic phenomenon they try to imitate and which originally had a genuine creative value, raising it to the level of a pattern but thus depriving it of any novelty.”

#

The Medium of Modernity

Taylor Stone

A book review for Sandy Isenstadt’s Electric Light: An Architectural History, on how artificial illumination changed the way we see the world in more than a literal sense:

… The intersecting inventions of electric lighting and cars created an entirely novel activity: night driving. … [N]ight driving created an unmistakably modern way of experiencing the world at night. Indeed, Isenstadt points out that through learning to manage this conglomeration of new technologies, and learning to understand the world presented via headlights, we became modernized in the process.

See you next week (maybe!) Regular, reliable posting will return by July.